Search the Community

Showing results for 'meantone'.

-

There's been a lot written about meantone tuning recently on this forum, but I don't think there are any practical audio comparisons. Since I have anglos in both ET and ¼ comma meantone, I've recently made a short youtube movie to demonstrate and hopefully demonstrate the difference. Unfortunately, I only have Bb/F anglos in both temperaments, so the recording will sound a tone lower than most people would be used to. I've selected four contrasting sorts of pieces and edited the video so that the differences can be directly heard. I've discussed some of the issues, so it is a bit on the long side, but I do hope it will help anybody who is unsure of the scale of difference between the two. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HT9fStxlbBQ&feature=youtu.be Adrian

-

I have just recieved my new wooden-ended Aeola TT from Theo Gibb. Apart from doing a brilliant job of restoration he has tuned it in 1/5 comma meantone for me. I am not aware of having heard an ec in this tuning before and I was apprehensive about doing it. After consulting on here I decided to go ahead and am glad I did. Chords are definately sweeter and more rounded with no harsh heterodyne beating, at least in the keys I normally play in. When there is any slight discord it is no worse than an instrument in ET (eg f#maj, a chord I never use). On the whole I am very pleased with this tuning and would recommend it to anyone who has doubts.

- 44 replies

-

And I did it, yet again, on one only last night... As a matter of fact I do Shay - in the meantone tuning that Jeffries used Eb and D# are two different notes, with around half a semitone between them, and you'll find the reeds are stamped accordingly. So, though Bb was the norm there, some players/original purchasers preferred to have an Eb in addition to the D#.

-

As you may recall I have recently rebuilt a previously derelict brass-reeded Aeola TT (as featured in my avatar). Having played this in for a while, I'm getting a feel for how the instrument plays and how it sounds. I'm already being inspired to work on more song accompaniment - the reeds' sound is rich and mellow, but not as loud as a steel-reeded 'tina, so I'm thinking it will be great for song accompaniment. It may not hold its own in a session - I can use my metal-ended steel-reeded Aeola TT for that. At the moment it is tuned to philharmonic pitch and I've just started to retune it to modern concert. But Geoff Wooff's meantone description of one of his 'tinas in another thread set me thinking could this be something I should consider for this instrument. What are the advantages & disadvantages of tuning to meantone? How might this sound in chords used for song accompaniment? (I have one song in mind that I think suits the key of Cm)? What about playing together with other instruments - fiddle, harp? What effect on playing technique might I expect? I guess also that having spent many years assuming that that D#/Eb are the same notes (and G#/Ab), playing meantone may take some getting used to. I suppose when reading a Eb or Ab in b-keys I play those notes, and not their # equivalents as I might otherwise have done. Similary when playing in #-keys I play the # notes and not the b equivalents. Thanks, Steve

-

Though by the time this one was made Wheatstone's were "Unless otherwise instructed" only tuning to "Standard International Pitch i.e. A.440" and hadn't been tuning to meantone for a very long time - it had been railed against as barbaric as early as 1855 by no-less than Hector Berlioz, and the revival of it is a relatively recent thing.

-

Hi all - hope someone can advise me. I am restoring a 20 key CG Lachenal Anglo circa 1885 and have got to the stage of tuning. The pitch seems to be somewhere around A447 and as far as I can tell the tuning is closer to quarter comma meantone than anything else. So rather than attempting retune the whole thing to ET A440, I have decided to use what seems to be the original tuning. Since I want to use it mainly to accompany myself singing and to practice and improve my playing skills this seems like a good choice. So far I have tuned the G row using G as the root note and it sounds very sweet to my ears. My question is, should I use C as the root note when I tune the C row, or would it be better to stick with G for the whole instrument, so that there is no variation in pitch when playing across the rows? If anyone has any experience of doing this or understands the theory well enough to explain it to a poor amateur folk singer who does everything by ear, I would be very grateful to hear you words of wisdom.

-

Thanks to coronavirus, I’ve finished a number of projects which have been sitting on the bench for too long and they’re now looking for a new home. Over the next few months, I’m looking to sell these and would like to offer them here first with the usual donation to Paul for the website. All Anglos apart from one; all button counts include the air key, all in equal tempered A=440 pitch unless otherwise stated Here’s what’s coming up; let me know if there’s anything you’re interested in and I can tell you more, send you some pictures and we can talk about prices. · Lachenal 33 key C/G Steel reeds, fancy fretwork · G Jones 32 key Currently in B/F# but could easily go either to C/G or Bb/F in modern pitch – nice player Now taken · Koot Brits 41 key G/D · C Jeffries 27 key Ab/Eb, metal ends, metal buttons ¼ comma meantone · C Jeffries 30 key C/G, metal ends, bone buttons · Crabb 27 key C/G, wooden ends, bone buttons · C Jeffries 39 key C/G, metal buttons originally built & tuned for a semi-pro player by Colin Dipper. Already Taken · C Jeffries 39 key C/G, bone buttons · Lachenal New Model 62 key MacCann Duet · Shakespeare 39 key Bb/F Crabb 30 key Bb/F, very fancy wooden ends · Lachenal 31 key C/G Brass reeds, simple fretwork · Lachenal 31 key C/G Steel reeds, fancy fretwork Alex West

-

Tuning an old instrument to 440

catswhiskers replied to Everett's topic in Instrument Construction & Repair

Totani. If you want sweeter sounding harmony then quarter comma meantone is probably the way to go. If yours is a vintage instrument the variation from equal temperament you mentioned may mean that it was originally tuned to some form of meantone. I have a 20 key Jones anglo which had considerable variation from ET. The closest tuning seemed to be quarter comma, so I went for that and wasn't disappointed. It sounds very sweet, particularly when playing chords. Having said that, I don't play with other musicians. If you do then maybe ET is better. John -

Concertinas Stagi MADE IN ITALY 100%

Ano replied to Mrs Simona Italia's topic in General Concertina Discussion

Hello Mrs Simona, I would suggest: try and improve your website. I am missing information about: * price * warranty/guarantee (for how long do you provide warranty on defects?, etc.) * general description (beginner's instrument, or for demanding amateurs and professional players; tonal description; speed and response: only slow playing? etc.) * materials * reeds (steel, or brass, ...) * bellows (5-fold, 6-fold, ...) * are the buttons bushed? or not? * absolute tuning (A at 440 Hz?) * tonal range (e.g. G to C) * tuning temperament (twelve-tone equal temperament, or some meantone temperaments ?) Also: some videos would be nice. Show your concertinas (and factory) on youtube. -

26 buttons oncertina?

Don Taylor replied to Francisco Escobar Bay's topic in General Concertina Discussion

I understand that the 'modern' Equal Temperament (ET) tuning is a modification of meantone tuning which in turn was a modification of Pythagorean tuning. ET was developed to enable instruments to modulate to any other key without playing a wolf tone, but there are many compromises made to achieve ET. Some might say that ET stands for Equally bad Tuning. Instruments like concertinas that can only play in a limited ranges of related keys do not need to accept the compromises made to achieve ET, they can be tuned so that, for example, thirds sound good and yet still be close enough in tune to ET that they can be played with ET instruments playing within their range. This is not the same thing as having multiple reeds sounding simultaneously with most of the reeds detuned from the main note so as to achieve a musette sound. The tuning for the main notes is still ET. There has been much discussion here over the years about the benefits of meantone tuning for concertinas and perhaps the former owner/player of your concertina had it tuned in a meantone tuning. If so, then I would leave it alone and consider myself lucky. Here is an example of a concertina like yours tuned in 1/4 comma meantone: -

I've got some decisions to make on an 1850s Wheatstone that appears to be still in an original Meantone tuning, and I thought I'd open them up for discussions. The instrument in question is from Greg Jowaisas' Pyramid Sale, with brass reeds and unbushed bone buttons. The first questions have to do with the buttons. I have to admit, I don't like the appearance of the dyed buttons, with black buttons for accidentals and red buttons for C. Options would include replacing the C's with undyed buttons, or possibly replacing all of the buttons. And then there is the question of whether or not to bush the buttons. Either change would deviate from the original historic state of the instrument (including what appear to be the original bellows), one purely cosmetic, and the other affecting the playing quality. I'm torn between restoring an historic instrment as closely as possible, and improving it (for personal definitions of improve). The second questions would be, what meantone tuning was it in. Time permitting, I believe Greg will be posting the current reed information (it is not in tune with itself at present, but notes which would be enharmonic in Equal Temperment are consistently off indicating some form of Meantone), if anyone is willing to weigh in on what the tuning looks like, that would be great.

-

As others have said, this was almost certainly tuned meantone, not equal temperament. I retuned a similar one recently, and put it in 1/5 comma meantone - see https://pghardy.net/concertina/lachenal_27590/lachenal_27590.html for details. It sounds sweet, and is within 9 cents of ET for the main keys I play in, so nobody will hear it as out of tune in a session. That link has a table of frequencies and shifts from ET.

-

More Renaissance Polyphony on Anglo concertina

adrian brown replied to adrian brown's topic in Concertina Videos & Music

Thank you Gilbert and Jim, it's nice to play again after a bit of a house-renovating hiatus. It would be even nicer to play for a live public, but that's not going to happen for a while yet... Gilbert, yes my baritone Anglo is in 1/4 comma meantone, with enharmonic d#s and ebs, as are most of my other Anglos. I think this music in particular would sound quite sad in equal temperament, and over the years, I've got used to meantone for other styles too. There are not many occasions where I find myself reaching for the equal tempered instruments. Adrian -

Different notes on push/pull on EC

Little John replied to Neil Thornock's topic in General Concertina Discussion

As Geoff points out, there are 14 buttons to the octave which means you can have both Eb and D#, and likewise both Ab and G#. With meantone tuning these will be tuned differently. Tuned to meantone an English can still play in all keys from three flats to four sharps, which is surely sufficient for most mortals! But to answer your question about Anglo-style buttons on an English. Yes, it's vanishingly rare but I know of at least one. Steve Turner's English has five buttons at the bottom end which have Anglo action. There isn't a clear logic to them (I've played it) but the aim seems to be to extend the range downward without making the instrument too large. On my own Crane system duet (which is closely related to the English) I have four Anglo buttons. Three are to extend the range downward without increasing the size. The fourth is to give me a choice of Eb or D# as it's tuned to fifth comma meantone. (It doesn't have the "duplications" of an English so it's "limited" to keys from two flats to three sharps. That's hardly a limitation at all, except occasionally an E minor tune calls for a B major chord; hence the D#.) LJ -

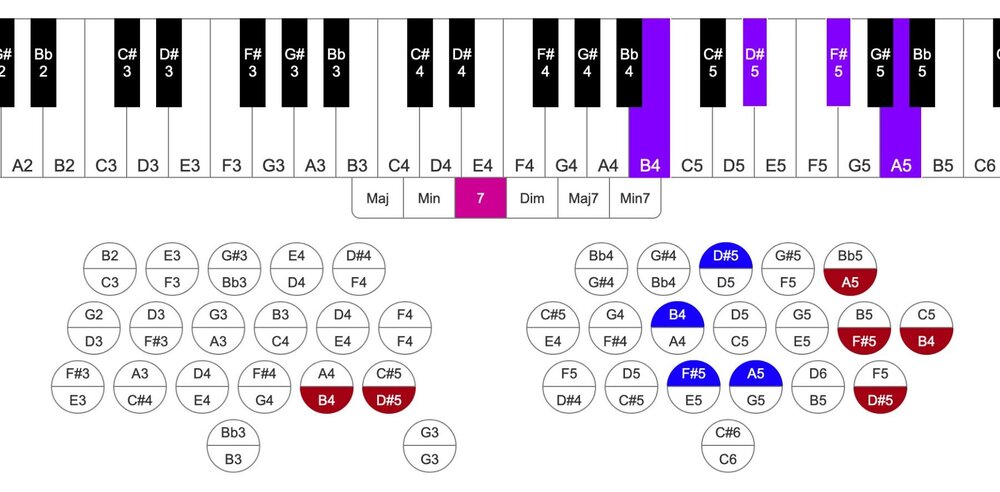

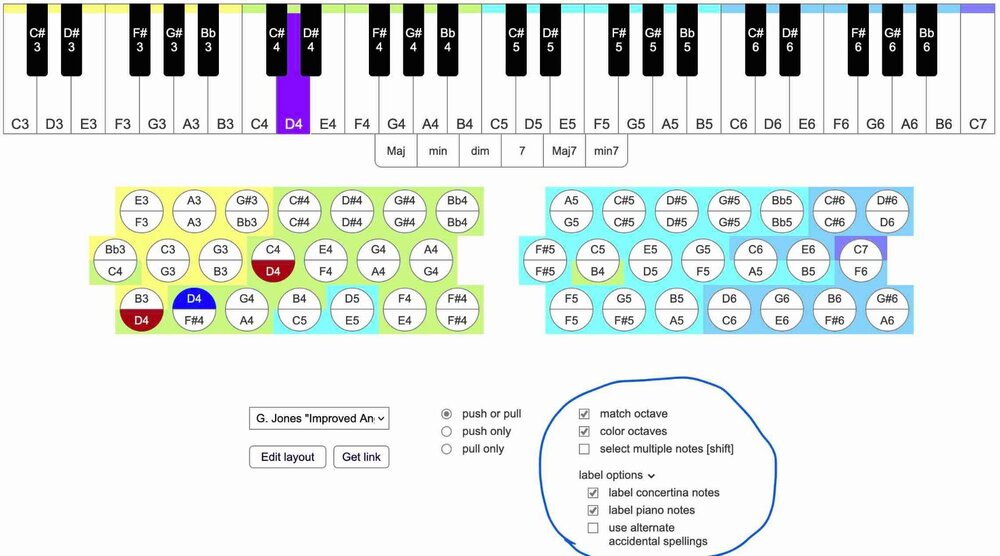

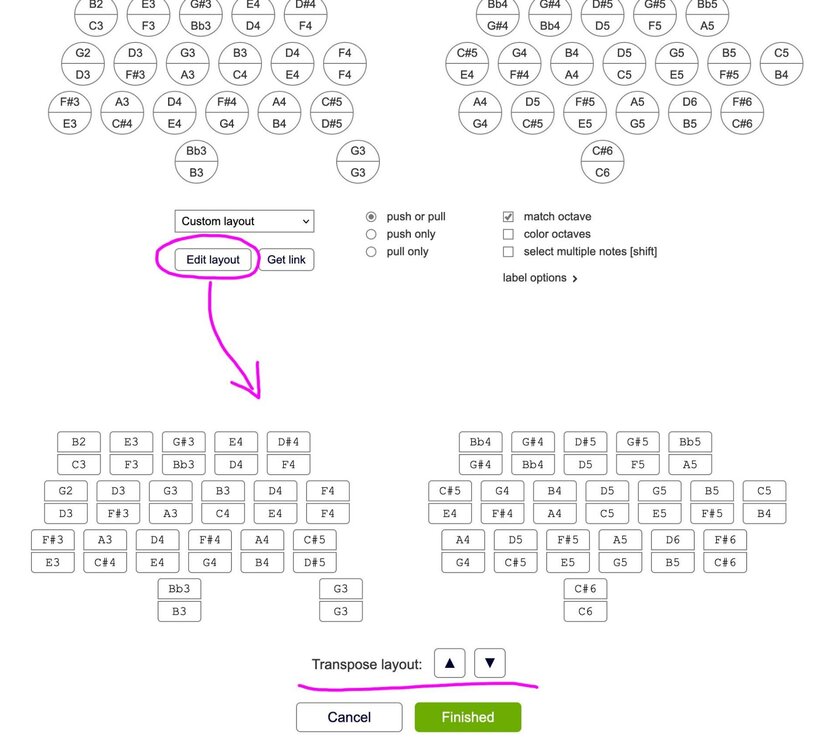

I finally got around to figuring out a way to do this! I think it has made the app just the slightest bit slower (it was already pretty slow 😒 ), but in my opinion the tradeoff was worth it. When you select a piano key, some chord options will appear below the piano keyboard. Clicking any of those will highlight the chord *in that octave* on both the piano and the anglo. You can still uncheck "match octave" to see all possible notes in the chord across the entire range of the Anglo keyboard. As a bonus, you can hear what the selected chord sounds like when you click it. At the moment, I've included major, minor, dominant 7th, diminished, major 7th, and minor 7th. I can add more if there's appetite. You'll probably need to do a hard refresh to see it work (ctrl + shift + r); I still haven't figured out what causes the weird caching issue. Update 2022-04-13 (Editing this post because I don't want to keep hogging the front page of the forum with minor updates) I've added/fixed a few more things that hopefully make this a bit more useful: Fixed the caching issue! Hopefully no more hard-refreshing required. Extended the allowed range of both keyboards to D2 - D7. Hopefully that covers pretty much all standard treble Anglos. New hard-coded keyboard layouts: 20-button C/G, G/D, D/A (these are useful for people who buy garage sale concertinas on a whim and then need to identify their tuning) George Jones' "Improved Anglo" Zulu Squashbox For custom layouts, the piano keyboard now automatically adjusts its range to match the concertina keyboard Selecting "push only" or "pull only" now completely removes the other bellows direction from view. This makes it easier to read and also reminds you that you aren't seeing all possible options. Optionally remove note labels on either or both keyboards Optionally re-spell accidentals to their enharmonic equivalents (for now this assumes equal temperament, sorry meantone folks!) Optionally color-code octaves! I've seen a few color-coded diagrams elsewhere and personally find that colors really do a good job of conveying an overall sense of the layout: Update 2022-04-18 I've just added the ability to transpose a layout up or down within Anglo Piano's allowed range (D2 - D7). This has already saved me a lot of data entry, and should be useful to folks who need a layout chart for an instrument in a weird/niche key, or who just want to see their own customized C/G layout in G/D, etc. To use it, just click "edit layout" under the layout dropdown menu:

- 77 replies

-

- 3

-

-

-

- learning anglo

- composition

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Gentlepersons, It is with great pleasure that I am able to share with you the recently-announced details of Thumtronics' forthcoming Thummer™-brand jammer. First, some terminology. “Jammer” is the name for all instruments of the kind that Thumtronics has invented. It is a generic word, just as are “piano,” harmonica,” and “guitar.” It is not trademarked; anyone can use “jammer,” without restriction, to describe instruments of this new type. “Thummer” is a trademark of Thumtronics Ltd for its brand of jammer. Just as one would say “a Fender® Stratocaster® electric guitar,” one would also say “a Thumtronics™ Thummer™ jammer.” They are both a mouthful, I admit, but the latter is no more so than the former. All jammers are electronic musical controllers or instruments which include 1. at least one thumb-operated effect-controlling device, and 2. at least one two-dimensional array of note-controlling buttons, the physical arrangement of which is optimized for a. the Wicki/Hayden note-layout, and b. use by the fingers of one hand. A couple of dozen Thummer™-brand jammer prototypes, as shown on www.thummer.com, exist today and are in the hands of Australian beta-testers. Hundreds more prototypes are expected to become available in March/April (although they may only be available in Australia). Thumtronics’ first commercial jammer – the Freedom™ Thummer™ jammer – is expected to become available in late 2006, at a price of AU$497, excluding shipping and any applicable local taxes. In US dollars, that’s about $365 at the time of this posting. Thumtronics’ first jammers will be musical controllers, which must be connected to a computer (PC, Mac, Linux – generically “PC”) via USB. Sound can then be generated either by a computer-based software synthesizer or from a MIDI-compatible hardware-based synth attached to the PC. Subsequent models may include sound-generating electronics, and thus be musical instruments. The Thummer™-brand jammer – henceforth simply “the jammer” – has three key benefits: 1. Expressive 2. Easy to Learn 3. Expands Musical Horizons Each of the benefits above is discussed on www.thummer.com, so I won’t repeat that discussion here. Instead, I will address those issues which I suspect are most likely to be of interest to readers of this forum. In a concertina.net posting roughly two years ago, Alan Atlas was kind enough to discuss many aspects of the concertina’s history and design. Two points struck me. First was that the Wheatstone English concertina probably was originally tuned (at manufacture) in (1/4-comma) meantone, only later being tuned to 12-tone equal-temperament. Second was Alan’s conclusion that the concertina lost popularity in large part due to its inflexibility of tone and timbre. Let me discuss the latter point first. The jammer has more flexibility of tone and timbre than any previous polyphonic instrument. The evidence supporting this conclusion is detailed at www.thummer.com, and is supported by quotes from relevant experts at www.thummer.com/reviews.asp, so I won’t detail those reasons here. Suffice it to say that the basic jammer supports five degrees of freedom (DoF) as shipped, with optional accessories raising that to seven, nine, or eventually thirteen DoF, without limiting polyphony. No other polyphonic musical instrument has this much expressive potential. That’s not hype; that’s a simple statement of fact. If “flexibility of tone and timbre” is so musically-important that the concertina’s lack thereof contributed to its decline in popularity, then perhaps the jammer’s strength in this area will tend to increase its popularity. The second point, regarding the concertina’s tuning, requires two brief digressions, one to discuss the Wicki/Hayden keyboard layout and a second to discuss the meantone family of tunings. Let’s discuss the Wicki/Hayden layout first. (You can find an image of the jammer keyboard here.) Robert Gaskins – for whom I have the highest respect – made a detailed comparison of the Wicki/Hayden layout to the Maccann layout a year or so ago, in which he concluded that: The compromises required to fit the “Wicki-Hayden” system onto a concertina, no larger than most people can play and light enough to be responsive, seem to limit or remove entirely most of its advantages. This is entirely true of the concertina, but not of the jammer (of which Mr. Gaskins was unaware, as it had not yet been invented when he wrote his comparison). A jammer’s buttons can be placed much more closely together than those of a concertina (for a variety of reasons beyond the scope of this discussion), so on the jammer three entire octaves of 19 buttons per octave can be spanned by the fingers of a single hand. Having 19 buttons per octave provides the same fingering in all 12 chromatic keys, eliminating Mr. Gaskins’ chief complaint about the Wicki/Hayden layout when applied to concertinas. Mr. Gaskins’ comparison also noted that electronic transposition could deliver the benefit of “having the same fingering in all keys” to a Wicki/Hayden concertina with fewer than 19 buttons, but pointed out that electronic transposition could give the Maccann layout “the same fingering in all keys,” too. This, he concluded, nullified the chief advantage of the Wicki/Hayden layout, that being its “self-transposing” nature. This conclusion is, however, based on a misunderstanding that is rife within the concertina community, that being that the chief benefit of the Wicki/Hayden layout is that “it has the same fingering in all keys.” That is not correct. The chief benefit of the Wicki/Hayden layout is that it is “isomorphic,” meaning that any given interval has the “same shape” wherever it occurs on the keyboard – within a key, as well as across keys. Being self-transposing is a consequence of isomorphism. Isomorphic note-layouts – and especially the Wicki/Hayden layout – expose the fundamental structure of the meantone family of tunings (my second digression). A meantone tuning is any tuning in which (a) the syntonic commas is tempered to unison and ( the major second is tempered to half a major third. There are an infinite number of meantone tunings. Many non-Western cultures play music using meantone tunings, including Indonesia, Thailand, parts of Africa, and (I think) Arabia. The most common meantone tuning in Europe, for about 400 years, was 1/4-comma meantone. It was so common that it is often called “meantone tuning” as if there were no other meantone tunings, but many others – 1/3-comma, 1/6-comma, etc. – were explored before 12-tone equal-temperament came to dominate Western music. More recently, academia has actively explored 19-tone and 31-tone tunings, both of which are also meantone tunings. It is very important to note that 12-tone equal temperament tuning – the tuning that is now standard on all piano-style keyboards, guitars, and concertinas – is also a meantone tuning. It is currently the most popular member of the meantone family. Now, we can tie together both of my digressions by pointing out that the Wicki/Hayden note-layout has the same fingering not just in all keys of 12-tone equal temperament, but in all keys of all meantone tunings. (This was discovered not be me, but by Andy Milne.) Having the same fingering in all meantone tunings, combined with electronic music synthesis (which can produce tones in any tuning), expands musical horizons in ways which are discussed elsewhere and therefore will only be summarized here. This combination of isomorphism and electronic music synthesis allows musicians to conveniently explore: (a) the music of many different cultures and times on the same instrument, eliminating the need to acquire and master each individual culture’s different instruments; ( the use of “tuning progressions” as musicians of the Common Practice period explored the use of “chord progressions” and “key modulations,” and © the use of dynamic polyphonic retuning across the range of meantone tunings as an expressive effect in real time (like pitch-bending or wiggling a whammy bar). One might wonder, “these other tunings all sound like crap, so who cares?” While it is tempting to dismiss such musings as being merely ethnocentric, it is more practical to say that (a) consonance (“not sounding like crap”) is the result of aligning a timbre’s partials with its tuning’s steps, or vice versa (as per Sethares), and ( by using electronics/software to "temper" the partials of a given sound into alignment with a given meantone tuning, the resulting combination of meantone tuning & timbre be as consonant as is the combination of Just Intonation and harmonic timbres. Alternatively put, "yes, these tunings sound like crap when played with the wrong timbres, but we can electronically temper any timbre to sound good in any meantone tuning." One might similarly wonder, “but don’t meantone tunings have ‘wolf intervals,’ which restrict their use to only a few keys?” Yes, if (a) one tries to shoehorn a meantone tuning which requires (say) more than 12 tones per octave onto a keyboard that has only 12-note-controlling devices per octave, and ( electronic transposition is not available. Those restrictions imposed wolf intervals on meantone tunings used on piano-style acoustic keyboards. The jammer, having 19-buttons per octave and electronic transposition, has no wolf intervals. Alternatively put, "don't worry about wolf intervals -- they don't exist on the jammer." Thumtronics’ innovations could prove to be a milestone in the history of music. For over 500 years, music theorists and instrument makers have struggled to find the ideal balance between beauty (perfect consonance) and freedom (unrestricted modulation). - They could temper their tunings, but without electronics, they could not temper their acoustic instruments’ timbres. We can (as per Sethares, ibid). - They could shoehorn meantone tunings onto the piano keyboard, but without isomorphism and electronics, they could not deliver an arrangement of note-controlling devices that delivered unrestricted modulation. We can. The jammer’s novel combination of isomorphism and electronic music synthesis resolves this centuries-long struggle, delivering the beauty of consonant intervals and the freedom of unrestricted modulation. But, wait! There’s more. :-) While the jammer’s isomorphic keyboard is easy to learn to play without any notation, or with traditional notation, its combination of isomorphism and electronic transposition allow the use of a much simpler (and more powerful) system of displaying musical information we’re calling the ThumMusic™ System. Many expert music educators are very excited about the potential of the System. The combination of the jammer and the ThumMusic™ System could make music significantly easier to learn, giving more people than ever the ability to understand and create music of their own. In summary, then, the jammer’s expressive power should appeal to working musicians; its ease of learning should appeal to novices and music educators; and its expansion of musical horizons should appeal to creative artists – categories which overlap in many individuals, of course. If you would like to learn more about Thumtronics’ innovations, please visit www.thummer.com. If you’d like to help, or be kept informed, please join the ThumClub™. If you'd like to consider investing in Thumtronics Ltd, see our online Offer Information Statement. Looking forward to the concertina community’s response, I remain Sincerely Yours, Jim Plamondon CEO, Thumtronics Ltd The New Shape of Music™ P.S.: You can also find some videos of the jammer online, but their audio and video are out of sync. When the problem has been resolved, more and better demos will be made available.

-

@DaveRo pointed out via email that an upside of using a tone generator as opposed to a soundfont/individual recordings is that it would be able to better support instruments with non-standard tunings. Due to the way the piano keys are matched to the concertina buttons in the app, I had to be consistent about naming notes (e.g., always using "G#" instead of "Ab"). I'll be thinking about this for future versions. In the meantime, if you're using a meantone-tuned instrument... I'm sorry! 😅

- 77 replies

-

- learning anglo

- composition

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Tedrow G/d Meantone Tuning

Paul Groff replied to Bob Tedrow's topic in Instrument Construction & Repair

Hi all, I think there is a lot of confusion in the discussion above, which is not surprising as you will see. Since there now seems to be wide interest in the subject of unequal-temperament for concertinas, some here may appreciate a little more discussion of these issues (in more depth than I took to provide above). It is a complicated subject and it doesn't help that some major music dictionaries and other references that people might logically consult have made gross errors that have propagated in the literature (and in music education generally) for decades. For example, Grove's dictionary and the Harvard dictionary of music both are misleading on different aspects of equal vs unequal temperament, enharmonics, etc. First, if we are going to be very precise in this discussion I should briefly correct a couple of omissions of detail from my own post above. I don't like to edit posts once there has been a reply because this can take all intelligibility out of the discussion as recorded in the thread. See points under * below for these corrections and additions. These points are all for the sticklers; they are important but in an attempt at brevity I didn't want to bog down in them when making a couple points to Bob yesterday. Now, in response to Dirge, Chris, et al: I. Different keys do sound different even in true equal temperament (if the pitch of "A" is kept constant), because they will be placed in a different part of the instrument's range and will require response from different parts of your auditory apparatus. Neither musical instruments nor ears respond linearly (in timbre and other variables) to changing frequency, and sometimes they are spectacularly nonlinear (for that matter, so may be the acoustics of the room). Even if a piano is truly in perfect ET every different key will differ somewhat in timbre (tone quality) as well as frequency. Not to be forgotten is that piano technique involves very different motions in the different keys. For a piano player to truly be playing "the same piece in different keys" with *exactly* the same timing, attack, etc. for each note can be very, very difficult. That also might possibly account for a different mood heard by a listener. II. But there is a different question when the temperament is unequal: whether the relative intervals among the notes of the scale are the same or different when changing key. Actually, in regular meantone temperaments there are no differences in the internal intervals between the key of C (for example) and any other key, *as long as the correct notes are present on the instrument.* If you are playing music that stays in one major key with no accidentals you will be using 7 different named notes, maybe present in multiple octaves. A 1/4 comma meantone temperament with 12 notes to the octave might include the notes: C, C#, D, Eb, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, Bb, B. With these notes you can play in the major scales of Bb, F, C, G, D, and A. Within each of these keys, the pitch relationships among the notes of the major scale will be identical (again, as long as the music requires no accidentals). The average pitch of each of these keys will be different but the internal pitch relationships are the same. So, (except for the real and important issue identified in my paragraph labeled "I" above), every one of these keys should "sound" the same in such a musical test, though the music will be transposed up or down in frequency. In comparing a meantone-tuned piano to an equal tempered piano there will be differences in how individual notes and how individual intervals sound (in general, major thirds much sweeter in meantone, perfect fifths a little more active in meantone since narrower), and also, as I mentioned yesterday, the average pitch of the keys in meantone will be a little different than the average pitch of the keys in equal (the entire scale of Bb on the meantone piano may be on average a little sharp to the same key played on the ET piano, and the entire scale of A may be flat on average relative to the same scale played in ET -- depending on where the "center pitch" of the meantone piano is set). III. Where there are real differences in "the tonal colors of the different keys" that depend on actual *differences in relative sizes of comparable intervals from one key to the next* is in the well-temperaments, modified meantone temperaments, and related tunings. This is a hard concept to grasp. But consider the fifth interval from "doh" to "sol." This has a certain "size" in ET and it is the same in all keys within ET. It has a certain "size" in 1/4 comma meantone (a little less than in ET) and again it is the same in all keys within 1/4 comma meantone (if the "correctly spelled" enharmonic notes are available). But there are other tunings where the fifths are different in "size" from key to key within the same tuning; for example, C to G might be "just," D to A a little narrower (as in ET), E to B narrower still (as in 1/4 comma), etc. In these latter temperaments (including "well-temperaments," which are neither equal-tempered nor regular meantone temperaments), which seem to have been very important in European music from Bach's day or before through the early 20th century (or later :-), there really are "different colors of the different keys" that are due to very different proportions of the intervals of the scale. A lot that has been written about the different "sounds" of different keys dates from the period in which such temperaments were dominant in European art music. Hope this very short discussion might help those who raised questions find their way into the literature on this subject. There is a lot on the web and I like the big book "Tuning" by Jorgenson which your library might have or be able to order for you to study. Here are just a couple interesting links from one google search I ran: http://www.kylegann.com/histune.html http://www.albany.edu/piporg-l/meantone.html http://scilib.univ.kiev.ua/doc.php?6604172 Paul * Fine points that should be added to my previous post to make it more precise: 1. Actually there is no circle of fifths in meantone, and I should have re-worded my sentence to prevent that misinterpretation. When I mentioned "circle of fifths," I was getting at how the meantone-tuned concertina will compare with ET instruments as *the latter* move through *their* circle of fifths. In meantone, when you progress along the *chain or spiral* of fifths from Eb, Bb, F, C, G, D, A, E, B, F#, C#, G#, D# you just keep going -- because the D# you just played is well flat of the Eb with which you began. 2. Actually Jeffries and (John, et al.) Crabb may not literally have offered their customers alternate enharmonic A#/Bb that "often" -- these would be the commonest duplicates on their anglo layout if keyed for G and D, but in fact original G/Ds are probably not that common. More precise would be to have written that Jeffries and John Crabb often offered the alternate "re #/mi b" when the anglo was made in the keys of "doh/sol." But I'm not sure this would have gotten across without the concrete example. -

Moved to General Discussion

-

Hi everyone, I reckon you trust me being well aware of previous discussions insofar. Here‘s what I‘m after: I‘m just acquainting myself with this beautiful brass-reeded instrument, which appears to be in higher pitch and meantone tuning. However, having adjusted my ears to the different sound of temperament tuning, I still notice some slightly odd notes. So I upgraded my tuner, tried quarter comma meantone tuning and tried to calibrate the pitch. Result is that every note (with the exeption of the two added enharmonic notes of course) falls well with the plus/minus 5 cent range, but only if I choose 449 (instead of 452 as expected). I do not intend to take it down anyway, as I want to use it as a solo instrument, or to accompany my (or my wife‘s) singing. So would you recommend to find the best-fitting pitch (probably 449) and touch just few reeds which are actually annoying me - which would rather mean to take them up one to three cents? Is quarter comma meantone the appropriate approach? Unfortunately, I can‘t try 1/5 comma as my tuner doesn’t provide that, but from what I’ve read 1/4 comma is what has been in use around 1860 - which I‘m told the instrument has been fabricated... Thank you in advance for any input - ?

- 34 replies

-

- george case

- quarter conma

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

old pitch and temperament - again

cboody replied to Wolf Molkentin's topic in Instrument Construction & Repair

Well...just to clarify, or muddy, things a bit. My term scale below refers to the major scale. 1. The reason for a particular starting note being chosen with mean tone tuning is that the farther you deviate from the scale of the chosen starting note the farther the scale sounds out of tune and the worse important chords will sound. 2. 1/4 comma and 1/5 comma meantone tunings arean attempt to deviate enough to allow the advantages of meantone tuning to apply to a wider range of keys. 3. The range of good sounding keys is narrower with 1/4 comma tuning, so realize that if you leave it tuned that way you’ll want to be sure you’re happy with the available keys. I’m not advocating you change the tuning, though 1/5 comma would be my choice. 4. You can see from the above why knowing the chosen starting point is crucial. 5. If your tuner gives Hz I’d recommend you get those numbers for the entire instrument. It should help determine starting note. And/or if your tuner allows you to set the starting pitch for the 1/4 mean try each starting note and frequency and check the scale for the other notes. The starting note used will be the one where the scale deviates the least. Then you will know which notes need adjustment. 6. The wolf tone you refer to is mediated by the 1/4 or 1/5 meantone tuning, so strictly speaking it doesn’t occur anywhere. I believe that term is usually only associated with Pythagorean tuning, but I might be very wrong about that. hope this helps!- 34 replies

-

- george case

- quarter conma

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

old pitch and temperament - again

Wolf Molkentin replied to Wolf Molkentin's topic in Instrument Construction & Repair

Further examining seemed to confirm my understanding that meantone tuning in „the key of C“ (or in fact whatever; see below), according to my tuner, is providing a just major third above (E) and below (Ab, whereas G# to C wouldn’t form a third anyway, but a diminished fourth) and the ? (as mentioned above) between G# and Eb (in fact a diminished sixth). Setting the tuner to „the key of D“ resulted most notably in indicating the Bb as way too sharp (because apparently an A# would be expected instead), and I reckon the Eb would deemed wrong as well this way... (whereas setting it to „the key of A“ should even compromise the F, interpreting the respective note as an E#). This leads me to the notion that the odd intervals in meantone temperament are depending not from the tuning of white and black keys (the latter in two - enharmonic - variants each), but where the sharps and the flats end resp. are being replaced with one another. Re the tuning I should be fine with 1/4 comma meantone „in the key of C“ (which seems to just say: no shifting in the circle of fifths, just the normal D-centered, as known from ancient Pythagoran tuning, or A-centered if we would choose D# over Eb) then, regardless of the root note (which may be A). It‘s just the slightly odd sounding notes that are indicated as flat... Objections, corrections? Thanks again in advance - ?- 34 replies

-

- george case

- quarter conma

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

old pitch and temperament - again

Geoff Wooff replied to Wolf Molkentin's topic in Instrument Construction & Repair

Nice concertina Wolf !! Firstly I never use these pre-programmed temperaments that modern tuners provide and I suggest you question your tuner as to what values it is actually ascribing to each note. If the actual basis of its 1/4 Comma setting was C then it might well show you a best fit of 449 hertz for A. When actually the pich might be is closer to 452hz. with A as the centre point of the Meantone values. I'll admit I have not thought this through completely yet but see if you can discover what your tuner is programmed to. Electronic tuners are made to measure 12 notes to the octave and the EC has 14 so this is the way I would proceed: Turn off the 1/4 Comma programme and start with the ET setting. Measure the pitches of the D#'s and Eb's and find where they are equally sharp and flat and see if the A's are sitting at the centre point between the D#'s and Eb's. That should tell you IF A is the Zero point of the Meantone and what pitch it was originally ( or the last time) tuned to. So usually Meantone EC's are tuned with the A as the zero point , because this gives a reasonable spacing of the enharmonics.,.. which might be sharp or flat of today's standard pitch... If you require actual 'cent' offsets for each note I have them to hand or you'll find them on the forums somewhere.- 34 replies

-

- george case

- quarter conma

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Meantone Tuning on Anglo Concertina

adrian brown replied to Mike Hulme's topic in Instrument Construction & Repair

Hi LJ, I'm an instrument maker working principally with renaissance woodwinds, so 1/4 comma meantone is sort of in my blood, since it was the only tuning system in use until around 1600. However like you, I've never found it an insurmountable problem, even playing with other instruments, although on one occasion I did wish I had an a# too (But having Bbs in both directions is far more important. I don't know if you have seen my youtube video comparing 1/4 comma and ET? It was my rambling attempt a few years back to demonstrate the difference in a practical way. I've never tried 1/5th comma so I can't really comment on the difference between the two, but it would be interesting if somebody with both made a similar video, or perhaps even comparing ET and 1/5th comma meantone. Adrian -

Meantone Tuning on Anglo Concertina

adrian brown replied to Mike Hulme's topic in Instrument Construction & Repair

This was something I ponded over for a long time Stephen, when I started tuning my anglos in 1/4 comma meantone. If you do it as your suggestion, you end up with instruments that can't be played together, because their overall pitch is sharper or flatter by the offset you've given the A. I plumped for tuning all my A's to a-440Hz and simply moving the wolf around with the different tunings. So with my CGs it's Eb/D#, with my GDs it's Bb/A# , on my Bbf, C#/Db and on my FC G#/Ab. This has the advantage that on all my anglos, the wolf is on the same fingerings and the good thirds/bad thirds are too. As I am using the Jeffries 39 layout, I have the flatter of the two on the push and the sharper on the pull - not quite as versatile as the English layout with its 3 enharmonic possibilities, but I find it gets me far enough for most of what I want to do. Adrian Meantone temperament calculations for anglo concertina.pdf

.thumb.jpg.e5ef9a111c1064c0bbea848f22aab7fe.jpg)