-

Posts

308 -

Joined

Everything posted by Stephen Mills

-

Are Vintage Concertinas Underpriced?

Stephen Mills replied to fiddlersgreen's topic in General Concertina Discussion

Is this Phoebe Carrai by chance? Her website describes a similar cello. I've been visiting her site very regularly for the past 6 months because you can play her Bach cello suite recordings from there. (Although I've been playing the Prelude from the 1st suite for 25 years on guitar, I can't get it right on the Hayden duet, so I've been trying to rethink it with a real cello version in mind and ear.) -

Run About, Scream And Shout

Stephen Mills replied to Rhomylly's topic in General Concertina Discussion

Hmm, if you mean Clovis, how would tell the difference? I drove through there 3 weeks ago for the first time in about 20 years, but saw no smoldering adobe. You might be interested to know that Buddy Holly and also locals Jimmy Gilmer and the Fireballs recorded their hits in Norman Petty’s recording studio on 7th St. in Clovis. You could always quote “Sugar Shack” or “Bottle of Wine”, if you’re old enough to remember those. Insinuating one of them into Arkansas Traveler could be a fun musical task. The Fireballs were just getting to be big-time when some British lads started to have some success on the charts. -- Clovis H.S. grad – 1967 Oh yeah, best of luck! -

I therefore don't think the soundtracks from existing CDs should be posted, nor commerical offerings etc. And I think the player should be a C-Netter. The value of this sort of page is that its primarily for enthusiastic amateurs or semi-professionals (?) so share their playing, to learn from each other, to be inspired by people who play better than oneself etc. Tom I agree in principle with what you say, Tom, but the overarching concern should be whether the recordings are in some way useful to c.net members. When others noted a lack of many duet examples or Maccann players, I suggested to Henk that he link to John Morgan's web-posted Maccann piece "goronwy owain - ffarwel i'r marian". Not a cnet member, to my knowledge; from an existing cd not on the c.net music page, last I looked - I still think it's an appropriate inclusion. Great job, Henk. I've complimented you privately a couple of times, but public praise doesn't hurt, either. The fact I've learned a few of these pieces after hearing them posted speaks to the success of your project, I think.

-

I feel like I’m playing into Jim Plamondon’s hands by responding to a portion of his thread blitz, but I have to say that my experience with the Hayden layout supports his assertion in this thread. I not only don’t have absolute pitch, like Stuart, but I have a bad ear due to years of over-reliance on printed music. I’ve played classical guitar since the mid-70’s, and am still very slow at picking out melodies on it. I picked up mandolin a few years thereafter and became better at the task on mandolin after a few months, probably because I played the mandolin in fewer positions, played simpler melodies on it and it’s wholly in fifths, i.e., the task is more consistently isomorphic. I do less well, but OK, on the Anglo (3 years now), probably due to more devoted effort to develop my ear training on that instrument, but here’s the thing. After only 3 weeks playing the Hayden system, it had already become the best instrument for me for playing by ear. My surprised and pleased interpretation was the same as Jim Plamondon’s – the regular mapping of specific intervals onto specific finger movements helps me a lot. My guess is that this effect would small or nonexistent for those who have already developed good ears for reproducing relative pitch by voice or other instruments. Extraneous to this thread, I love the Hayden, but there are of course prices to pay for any system. I don't like having to cross the fingerboard and go down a row to play an accidental, instead of moving a small and fairly consistent distance as on guitar, piano, etc.

-

How To Get The Blood Off Your Concertina

Stephen Mills replied to David Barnert's topic in General Concertina Discussion

Good one, Andy. There are so many good candidates.... I like Gershwin's "Let's call the whole thing off". However, for no good reason I'm guessing "Somewhere over the rainbow". revised guess: "Amazing Grace". I asked 3 people. The only answer I got was "Yesterday". Hmmm, the frontrunner? -

How Many Concertina Players Are There?

Stephen Mills replied to CaryK's topic in General Concertina Discussion

9 cnetters have admitted to playing the Maccann system - besides yourself, there's Ivan Viehoff, Alex C. Jones, Old Squeezer, Stuart Estell, Wes Williams, Robert Gaskins, Jim, David Cornell and tony, if you're curious. Outside of cnet, John Morgan, Bob Webb, Sean Minnie and maybe Stephann van Zyl are some performers on Maccann. Listen to this beautiful tune on Maccann from John Morgan's band Megin. (Click on John Morgan's name here.) Cnet members who play Anglo have to be a tiny fraction of Anglo players worldwide, almost certainly less than 5%. The cnet percentage of English players would also be low. It would be dangerous to assume similar percentages for Maccann, but I'm betting even 200 players is a low estimate. I suspect there may be more hidden Maccanns out there than any other duet system, unless it's Cranes. Cranes? At least 12 on cnet. Performers include George Flink, Andrew MacKay and Dick Wolff. Jeffries? I know of 2 players in the E. Texas/Arkansas area alone. There's at least 7 on cnet. edited to remove a shocking case of grocer's apostrophe. -

Thanks, Stephen! My part of England is Devon, in the Southwest, not the Midlands. This is quite close to Sidmouth, of Folk Festival fame. There is only a single blue "Duet" dot in the whole of Devon on your map and I thought this was Geoff Lakeman (username "Lakeman"), but I just saw from his profile that he hasn't submitted his location or type of concertina. Geoff plays (as opposed to me, who's only trying to) the Crane Duet and lives about 5 1/2 miles from me! (This must make Yelverton - our postal town - the place with highest Crane Duet player density anywhere in the country, I reckon! ) Hmm, puzzling. I remember your case, because Dartmoor doesn't come up in Mapquest, being a region, probably, and not a city, but you were listed in my database as being near Plymouth. So either I didn't plot you or Geoff Lakeman, who I also had listed as being in the Plymouth area. Now there are two dots there, and ennistraveler's as well in Sweden. [digression] I wonder how many of you duet players have had prior keyboard experience, most I expect. I haven't, and for me, the hardest part of learning the Hayden these past few months is the hand independence part. Not for written music, but for comping against melody in the RH. [/end digression] There's science and there's fun, Jim. I do my science during the day. What I do here tends closer to the barroom argument. (I'm fortunate the science is also still fun after all these years.)

-

You are already on the map. Members who provide locations and type of instrument information in their profiles, or even their posts, are placed on the map as soon as I get 10-15 needing placement. Sadly, your part of England (is this what's called the Midlands?) is so overcrowded with big dots now as to lose all utility. At some point, I may expand this region as I have Old and New England previously. See the map thread, pg.3, for an interesting comparison of UK light pollution with its concertina density, thanks to Peter Brook. Trivia question: Without looking at the map, what are the only 2 countries with more than 5 c.net members which have more English players than Anglo as represented by the limited map sample? Players of both systems are counted in both tallies. Reto Werdenberg also lives in Basel. His only post, I think, details what instruments he plays. Oh, I see Henk has identified him as I compose this. Encoded answer to question: XXAXXDXXAXXNXXAXXCXX and XXSXXDXXNXXAXXLXXRXXEXXHXXTXXEXXNXX

-

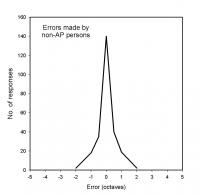

I don't really disagree, David. Any difference in opinion we have on this is subtle at best and not related to misunderstandings of measures of central tendency. Incidentally, the parenthetical expression "single most common" were my words; I missed it when I was inserting the italics, and I also reworded fairly freely elsewhere for conciseness. There can certainly be no argument with the statement that 0 errors was the modal response - that's a concrete observation in black and white on the figure. (0 is also virtually the mean and median, although I did think I detected a very slight imbalance to the high side). Why your point must necessarily be correct is that if the participants had absolutely no sense of pitch, the distribution would be completely flat - in other words, all responses would be equally probable. My point was that, in the absence of AP, the responses might be, and sometimes were, an octave or more off. If the subjects had enough pitch sense to be at least somewhere in the ballpark, and I think most of us have that much, then any lack of a systematic bias towards higher or lower would lead to a centering around the true pitch. This effect could occur with pitch sense so weak relative to AP as to be hardly worth discussing as rudimentary AP, IMO. This ability to perform anywhere greater than random may be all the authors were claiming, although I took it to be a slightly stronger argument. I think the data of individuals rather than the whole population would have been more interesting. The central limit theorem of statistics does suggest that the distributed response of a population will center around the mean; without bias (a skewing tendency), this will also be the population mode. The combined distribution of a lot of individuals most of whom do not center around 0 errors could, and probably would, combine to center around 0.

-

I have just stumbled across a review in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol 9, pp. 26-31 (2005) entitled “Absolute pitch: perception, coding and controversies” by Daniel Levitin and Susan Rogers of McGill University, Montreal. I found it very interesting and so I have resurrected this thread, quoting below many of the authors’ provocative assertions. I have no special expertise in this area and won’t attempt to defend or further interpret any of the statements. My occasional comments appear in italics. Absolute pitch (hereafter referred to as AP vs. relative pitch, RP) is defined as the ability either to identify the pitch of a tone presented in isolation or to produce a specified pitch without external reference. AP occurs in 1 in 10,000 people. Sometimes regarded as a mark of musicianship, AP is in fact largely irrelevant to most musical tasks. Being unable to turn it off, many possessors of AP perform dramatically poorer at judging whether a melody and its transposed counterpart are the same, a task that many non-AP musicians accomplish with ease. Some find songs transposed to unfamiliar keys disturbing, as if one day you went to the market and found bananas to be purple and tomatoes blue. Growing evidence suggests that many people in addition to AP’ers may have stable, long term auditory memories for pitch. This is 1 of the components of AP, called “pitch memory”, while AP possessors have the additional component of “pitch labeling”. Some of the evidence: When people without AP are asked to identify a pitch or key, the modal (single most common) response is the correct one (see figure). [I personally am not quite convinced by this. The range of response varies over 4 octaves. Does the tendency of the population to center over the true pitch mean that people possess rudimentary AP (some memory, without labeling), or that the population tested is as likely to guess high as low, and so centers around the true pitch. I did not check the original article to see if they had considered this.] If asked to sing popular songs that currently exist in only 1 key and thus have an objectively correct pitch, most people sing at or near the correct pitch. Quite often, this is tied to the lyrics. For example, people tend to pitch the word “hotel” correctly at G when asked to sing “Hotel California”. [no accompaniment or external references are present, remember.] AP is automatic [not further defined in this article], categorization occurs without deliberation, is accompanied by large differences in speed of performance compared to non-AP attempts, and can be done easily while engaging in other tasks. AP’ers as a group do not have exceptional pitch acuity. Also, AP is neither “absolute” nor “perfect” in the ordinary uses of those words. AP’ers often make octave errors and semitone errors (confusing tones 6% apart). It appears AP is not an all-or-none ability, but exists along a continuum. Musicians not claiming AP score up to 40% on pitch labeling tests, where 1/12, or 8.3% is chance. Even true AP’ers, who score better than 90% in naming pitches, are no better than other musicians at noticing when one tone is out of tune with respect to another. Hence, there is nothing “perfect” about AP – it is just the ability to place tones within nominal categories with a high rate of success. Some AP’ers can only label tones produced by one particular instrument (usually piano, of course, and sometimes called ‘absolute piano’). This suggests that their internal template is bound up with the timbre of that particular instrument, so presumably a life-long concertina player might have absolute pitch specific to concertina [insert joke here]. Some people have AP for only a single tone – often their tuning note. They can get good scores on AP tests by using RP for all tones but their one internal referent, but are betrayed by the increased reaction time for the other notes. Some people develop AP on mistuned instruments and will make constant errors thereafter. [This is truly sad.] Many animals, wolves for example, use AP to identify members of their own pack. Starlings and rhesus monkeys try first to solve pitch tasks with AP, but can move to RP if necessary. Monkeys, but not songbirds, are able to use “octave equivalence” in performing tasks. AP is acquired before the age of 9; no known cases exists of an adult acquiring it. Because piano instruction starts with the white keys, many AP’ers are best at these notes. Speakers of tonal languages (e.g., Mandarin Chinese) are more likely to have AP. Controversy exists as to whether AP acquisition requires explicit training or can result from incidental exposure to music. Most AP’ers report having acquired the ability without remembering how or when it occurred.

-

As probably even most non-Hayden players are aware, the Hayden keyboard is laid out so that any scale has the same fingering pattern (until the edges of the instrument intrude). A scale traverses 3 rows as, for example: {- - C - - - -} { - F G A B -} {- - C D E - -} The logical RH fingering for this, and that mentioned in the Gaskins article, is: {- - 2 - - - -} { - 1 2 3 4 -} {- - 2 3 4 - -} where 1,2,3,4 are index, middle, ring and little fingers. The trouble I find with this scheme is that the strong index finger plays only the IV note while the little finger plays both the III and VII notes (in the major Ionian mode). In fact, I find that on some tunes, my little finger is playing almost every other note over extended passages, while the index finger basically lays out. Now I've got pretty well trained little fingers, especially on the left hand, from 25 years of classical guitar, but this can hardly be ideal. I have investigated some compromise solutions, but Hayden players, what do you do?

-

Important Foundation Question

Stephen Mills replied to oDugain's topic in General Concertina Discussion

Playing it on the G row, a reasonable starting approach, leads to the problems you mention. I printed out this tune as you listed it and found it very well balanced for push/draw when played entirely on the C row. edited to add: except for the f#, which must be on the G row, of course. The difficulties in changing fingering you mention will go away with practice, particularly if you practice some scales with draw-only fingering and push-only fingering, within the capabilities of your instrument. Recently, I've been setting fingerings phrase-by-phrase, rather than on what row or scale I think looks most appropriate for the tune as a whole. The choices I make depend on various criteria, such as using strong fingers when possible, finding the best accents and phrasing, adding harmony notes, and optimal air control. Usually I can start and end a phrase with the bellows in about the same position, depending on choice of fingerings. This is not as easy on a 20 button, but I think seeing if you can start and end the phrase in the same bellows position is an excellent exercise, even if other musical ideas lead you to choose a different fingering eventually. -

How Many English Players?

Stephen Mills replied to Jeff Stallard's topic in General Concertina Discussion

And they are all expert at hiding it! <{POST_SNAPBACK}> And if all 150,000 were playing at the same time today, the din must have been unbearable even in Australia! Very funny, you two. Stephen, I've been giggling at your little joke all afternoon. I'm going to take a timely break from the fray in pursuit of 1 unassailable statistic: the number of concertinas in my household has increased by 1 this evening with the delivery of my Tedrow Hayden duet, and 1 unassailable fact: I have no clue how to play it but for a button diagram. (UPS delivered the concertina to the corresponding house 2 blocks north - if the honest resident had kept it instead of getting in his car and personally delivering it....) Welcome back from Sidmouth, you tired and happy lot. Wotcher, one and all. -

How Many English Players?

Stephen Mills replied to Jeff Stallard's topic in General Concertina Discussion

Malcolm and Nanette: this site states that “Approximately 150,000 people play the accordion in Australia today.” I wonder how that estimate corresponds to your personal experience of local instrument percentages and might influence your notion of how many concertina players there might be in Australia. ***WARNING*** ***WARNING*** ***WARNING*** No justification was given for the estimate given in the quotation above. It should not be accepted uncritically because it was found with a google search. Data found on the internet may be false, as may be the expectation of finding correct answers. Although I have repeated this estimate, I have made no attempt to verify its validity. I have no desire to create or perpetuate intentional deception resulting in injury to another person and accept no liability in this matter. ***WARNING*** ***WARNING*** ***WARNING*** -

How Many English Players?

Stephen Mills replied to Jeff Stallard's topic in General Concertina Discussion

Guessing is the antithesis of information gathering. REPLY: Estimating, or guessing, is a time-honored way to begin attacking seemingly intractable problems. It’s a beginning, not the endpoint. When you assume something might be true, then you begin to ask yourself what the consequences would be if it were true, examine whatever data you can bring to bear on the subject and then revise your estimate. In fields where you can’t usually generate controlled experiments, astronomy and paleontology, say, you often have to bootstrap yourself up. Consider how many times the ages of the earth, life, the size of the universe, etc. have been revised (almost always up). Consider our problem. Other lists of concertina players exist, in one form or another. Using one fairly limited list of 75 performers in the US, I find that less than 10% belong to c.net. (There are ancillary issues about recognizability of cnet usernames, but let’s not complicate things for now.) If you assume that nonperformers join at the same rate, then you’ve got an improved idea of how to relate cnet membership to the unknown whole. Even if you find the assumption specious, as I do, you can can begin to test the validity of the assumption, try to assess the magnitude of the error, or at least be attuned to the idea of testing it if some aspect of the data passed by you, whereas before you would have ignored it. Is that what you mean by "educated"? My own experience suggests two things: ... 1. There are more concertinas players in the world than we -- either the individuals reading this thread or any groups we individuals belong to -- are personally aware of. ... 2. We really have no good way of reliably estimating how many more. I draw these conclusions from my personal experience of 1) again and again discovering concertina players that I was previously unaware of and who are not members of any concertina-related group I was familiar with, and 2) over the years the rate of such discoveries has not decreased; if there has been any change, it has been an increase. I draw these conclusions from my personal experience of 1) again and again discovering concertina players that I was previously unaware of and who are not members of any concertina-related group I was familiar with, and 2) over the years the rate of such discoveries has not decreased; if there has been any change, it has been an increase. REPLY:Finding lower bounds is useful – if you’re interested in the answer, far more useful than total ignorance. If I knew nothing about the number of concertina players in Ireland and Israel, which have 3 and 1 members in the Atlas survey, I might conclude about equal densities. However, speaking to the ICA member in Israel, as I have, I find he can name only one other player in Israel. Shay Fogary or Stephen Chambers would presumably give a different idea of number of players in Ireland. I was pleased to have stimulated the discussion of players in Australia, although Malcolm’s rather precise estimate of 69% Anglo to 29% English had me believing he was pulling my leg at least a little. Admit that we really don't know, and that so far we don't even have the means of finding out? But today it seems culturally unacceptable to admit such a thing, even (especially?) when it's true. <{POST_SNAPBACK}> REPLY: Why do it? Because you’re interested, and find having some idea rather than no idea of the answer preferable? Because it’s fun? Should we leave off the study of consciousness now that attempts are being made to move it out of the realm of pure philosophy because it’s hard, with no clear end in sight? Both the wording and the error estimate (also a guess) gave fair, even overconservative warning to the reliability of the estimates. -

How Many English Players?

Stephen Mills replied to Jeff Stallard's topic in General Concertina Discussion

Thanks, Malcolm. This is the sort of feedback I had hoped to provoke. I initially had Australia higher (at least 350, maybe higher), but chickened out. On further consideration, I expect Germany has a minimum of 50 players, probably quite a bit more, so the "rest of the world" = 75 should be adjusted upwards, also. It's my opinion one tends to underestimate in general. How could it be otherwise, i.e., tell me how many players there are you never encounter in any way. I am most unsettled about the UK numbers, as I could find very little on which to base an estimate. -

How Many English Players?

Stephen Mills replied to Jeff Stallard's topic in General Concertina Discussion

Compare the following 3 estimates: Combining the figures Stephen Chambers quotes, so that the A figure is the total of A only players, plus combined A and E players , plus A and D, plus all three systems, and so on for E and D numbers. A 195 E 118 D 39, which break down as Crane, 10; Maccann, 8; Hayden, 12; Jeffries, 7; and other/custom, 2 A survey by Allan Atlas http://web.gc.cuny.edu/freereed/concertina_survey.htm showed: A 49 (with a 4:1 ratio of 30+buttons:20 buttons) E 21 D 7 So the Atlas survey shows a 2.3 ratio of Anglo to English. I think the c.net membership is probably a better estimate (1.65 A:E), though only about 1/3 of members have stated what they play, and Anglo-dominant Ireland and South Africa are underrepresented. John’s sample of ICA members: A 23.6% E 59.7% D 16.7% A:E = 0.40 So what’s going on here? For one thing, I think the ICA membership skews English, due to its origins (as perceived by me) in classical and music hall players - this despite considerable effort to be inclusive and also some notable past leaders who played Anglo. I’ve been thinking about Jeff’s question for a long time. How many concertina players are there in the world? Both the Atlas survey and the c.net membership are poor estimates - just consider there are only about 4 players listed in Ireland, none in Wales (Is there any concertina tradition in Wales?). I suspect the 2 players I know of in Israel represent a pretty fair proportion of actual players, while the 4 in Ireland are a small proportion of actual players, as are the 5 in South Africa and the 0 in the rest of Africa, where a decent tradition remains, especially squashbox. How would you go about getting such information? The only thing I can think of is educated guessing, with members estimating the number of players in their region from their experience. A shabby methodology, no doubt, but what else could be done? Before the Southwest Concertina Workshop, I knew of a half dozen concertina players in Texas - now I believe there are probably more than 25 (the map shows 8). How many more is the really thorny question. I say, for the sake of argument, that the number of actively playing concertina players (excluding Chemnitzers and bandoneons) is as follows: US - 1400 UK - 3000 Australia - 200 Canada - 50 Ireland - 350 Africa - 200 rest of world - 75 (TOTAL) 5275 plus or minus oh, 3000. Where did I get these numbers? Semi-educated guesswork based on crossreferences with independent databases, instincts, made them up if you will. You make your own guess and persuade me otherwise. Ebay is currently selling almost 4 concertinas/day (most best suited for concertina-tossing practice). Note: The c.net ratio of US:UK is about 2:1, but I believe there are probably a much higher proportion of unregistered concertina players in the UK. Conclusion: I think we can get a fair handle of relative percentages, though not within the subcategories of duets, but our grasp of absolute numbers is weak. I wonder what the relative percentage of instruments that come into Barleycorn Concertinas is, especially within the duet category? These are people who list two different residences, such as Ken Coles. Just call me Solomon. -

Stinson Behlen (1917-2004)

Stephen Mills replied to Stephen Mills's topic in General Concertina Discussion

Harold Herrington wrote: Stinson Behlen, my old friend I met Stinson Behlen back in the mid 1980's. I was playing banjo every week end with an Irish folk group and got this crazy idea that I would like to take up the concertina. I tried out several of the low end concertinas, made by Bastari or Hohner, and quickly realized that they would not be adequate, even with amplification, for the pubs we played in. It needed to be something with a lusty voice to compete with the background noise. I called Norman Seaton, president of the Texas Accordion Association. He recommended that I call Stinson Behlen in Slaton, Texas. That was the beginning of a long friendly and informative relationship. This would eventually lead to my designing and building my own line of concertinas. Stinson was a tall handsome man, I'm guessing about 6' 3" or more, with big hands and a big smile to match. He was a combat veteran of WW II, serving as a radioman in an infantry line outfit. He was a great musician, accomplished on the piano, diatonic,and button chromatic accordion. He built Cajun one row accordions in the old style, and they were excellent instruments. Stinson also was, in a manner of speaking, a builder of concertinas. I say "in a manner of speaking" because Stinson did not actually build them. They were built to his specifications in Germany, under his name. He also handled several other brands of manufactured accordion reed concertinas. Stinson did repairs on both English as well as accordion reed instruments. From what I understand his repair work was good. Stinson was a treasure trove of information on free reed's and free reed instruments, and for me he was extremely generous in sharing this information. He invited me to Slaton and taught me to tune, and some of the basics of free reed function. He loaned me his rare collection of free reed and accordion books. He showed me some of the tricks on building reed blocks for accordions and Italian style accordion reed concertinas. He had a fine collections of rare books on free reeds and free reed instruments, dealing primarily with accordions and harmoniums. All but one of these was written in a language other than English. I think he had a complete, or near complete, collection of the English "Free Reed" periodicals, as well as publications from Australia. I would love to get my hands on that collection. He also had a complete set of editions of the now defunct "Concertina & Squeezebox", formerly edited by John Townley and later by Joel Cowan. For a number of years Stinson was a contributor to that magazine. Everything Stinson wrote was written on an old fashioned upright typewriter. He was noted for vigor in his typing, and most of his letters came with the centers of the O's, D's and P's missing. He would bang the keys hard enough to cut the centers out. The insides of the G's and C's would be like a Florida ballot with a hanging "Chad". You could tell when Stinson's blood was up since the prevalence of missing centers and cut-trough's would increase. From time to time Stinson would go on a tear about one thing or another. He agreed with General George Patton that we should have gone ahead and kicked the hell out of the Russian Communist while we had the army and material in Europe to do it. He likewise did not have much love for the Jews, and blamed them for various financial ill's of the world. I did at one time consider pointing out to him that there is fine and upstanding Jewish family in Europe that bears the name Behlen. I thought better of that idea, and it is just as well that I did. I did manage to make Stinson angry with me on several occasions. My sins were more on the order of things I failed to do rather than things I did. The first Christmas after we met I failed to send Stinson a Christmas card. Evidently that really hurt his feelings. We had been corresponding on a regular basis and talking on the phone every week or so. Then there was this period of silence, no cards, no letters, no calls. I finally called him to make sure he was okay. With a little coaxing, he told me he was angry with me because I did not think enough of him to send him a Christmas card. It took about three phone calls to convince him that I did not single him out, and to make him believe me when I told him I did not send Christmas cards to anyone. I told him I would be pleased to hence forth send him a "Christmas letter" in lieu of a Christmas card, or at the very least give him a call on Christmas day. I told him I thought the Christmas Card industry was a contrived and artificial thing and designed to take the place of a personal letter at Christmas. And besides I said, the cards were way over priced. That seemed to satisfy him. Like so many young men returning from the horror of World War II, Stinson developed a drinking problem. It's little wonder, after having seen so much suffering and death, many returning veterans found escape in the bottle. When I met Stinson he had been in A.A. for quite some time. When I went to Slayton for the first time I checked in at the local motel, intending to meet with Stinson the next morning. I took a hot shower, put on fresh clothes, and made myself a Scotch before going out to eat. It was then I heard a knock on the door. I opened the door and there stood Stinson. I invited him in. I knew he was a non-drinker, but caught by surprise had no time to put the bottle out of sight, so as to not offend. We sat on the bed and talked for about thirty minutes, mostly about where we would eat, and what we would do the next day. When we stood to go he pointed at the bottle of Scotch standing next to the TV. He said, "I'm not trying to tell you how to live your life, but don't ever fool yourself into believing that whisky is your friend. It isn't.". I've never forgotten his words. I still have a collection of his letters, most with the O's and D's cut out. I would be please to share copies with anyone that has an interest. I hope that Stinson is happy where he is, and has possibly become friends with the Jewish Behlen's. Harold Herrington Herrington Concertinas Rowlett, Texas Tel & Fax 214-703-0409 -

Stinson Behlen’s name may not be well known today to many concertina players, but on this side of the Atlantic, before Carroll, Edgley, Herrington, Morse and Tedrow, there was Stinson R. Behlen, a maker of accordion-reeded instruments from his shop Southern Highland Accordions (later Southern Highland Dulcimers) in the small West Texas town of Slaton. Stinson R. Behlen, who died last year at 88, was probably most familiar to concertina players as a regular contributor to Concertina & Squeezebox magazine. His column, “The Bailin’ Wire”, covered a wide range of squeezebox-related items, often with a subtle hint from the editors that various colorful comments may have been edited a bit. At one point, he was making a unique A/A# concertina as well as other unusual designs, including a piano-style keyboard (initially unaware, perhaps, of the George Jones predecessor). I wonder how many other almost unknown people there have been working outside the UK in areas such as Australia, South Africa, and the western U.S, keeping traditions alive (or making their own) in concertina-sparse places and times. Behlen was well-known as a master luthier who made not only accordions and concertinas, but also mountain and hammered dulcimers, fiddles and guitars. His daughter recounts how at home she would field business calls from the likes of Lee Greenwood, and how she came home one day to find her father and Willie Nelson chatting away on the couch. The Dixie Chicks bought dulcimers from him. Behlen became interested in accordions early; he once said in an interview that “I would go out behind the barn to practice and my father told me not to come in until I learned something.” His daughter reports that “he was stationed in Scotland and Ireland during the war, never seeing any action. He toured accordion factories in Austria and Germany in his spare time while the other soldiers were off chasing women.” His son and daughter each own one of his last two free reed instruments, the Cajun Queen model, pictured below along with one of his fiddles and dulcimers. John Townley, a former editor of Concertina & Squeezebox, says: Stinson was one of the great characters of the squeezebox world in the days when there wasn't much intercommunication, especially in the U.S. If he couldn't get it, he invented it and pushed on in a truly frontier American mode. He must have lived to a ripe old age, seemed like he'd been around forever when I first encountered him decades ago. Rest well, squeeze on like new on the other side... C&S's Latin motto "Comprimere in aeternum" really applies here... A new name appears in some of the latter columns, that of Harold Herrington, whom Behlen was helping get started in concertina design and construction of tuning equipment, etc. If you consider that Stinson Behlen helped Harold get started, and Harold in turn helped Frank Edgley, it’s pleasing to believe that his influence continues to reverberate today. Harold has kindly contributed his reminiscences of his friend, which are listed in a dedicated posting below. I would like to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Melissa Sleeker in furnishing materials for this brief history of her father, Stinson Behlen, as well as Harold and John for their comments.

-

from Stephen Chambers in the concertina and women topic I’ve been researching (read “wasting copious amounts of time trawling the web) the diaspora of concertinas from the British Isles lately. Among the many interesting tidbits I’ve found are: A journey in steerage - 1904...[T]hese [irish emigrants] certainly possessed youth and high spirits, good nature, warm affections and a concertina to every dozen or so. The deck spaces of the “Cedric” are so huge that even the 1,700 third-class passengers did not crowd them, and ample room was offered for dancing to the music of these concertinas, every one of which on a pleasant day was in pretty steady service. Young and old danced until tired. and in History of the Darwin City Waterfront (post-1870) The camp had a great love of music. Nearly all the men played the concertina, some were flute-players. And surely they all sang! for night after night when work was over they assembled under a shady tree in the middle of camp and a regular musical entertainment took place... Re: the Australians: I presume these immigrants were primarily English (esp. as the author of the piece is named Harriet Bloomfield). What type of concertina would they have most likely played? Re: the Irish: Should we presume most of the Irish emigrants would be playing cheap German concertinas, which may be why not so many of this apparently massive influx of concertinas have survived? I also take it that the percentage of Irish families with concertinas must exceed the 1/12 number, as I would presume that the displaced and disposessed would be less likely to have a concertina. Some, in fact, may have been like this immigrant fiddler: Ed McDermott was born on April 2, 1896 in Corrawallen, County Leitrim, Ireland. This is just outside the larger town, Ballinamore. His father was the local constable and also a fiddler, from whom Ed learned the instrument and attributed his style. He played at the local parish dances, just like many of the other lads. The period of his youth, however, was marred by the political turmoil erupting in Ireland prior to the Easter Rebellion of 1916. He unwillingly left the country, as he said, "on the run" in 1915. As Mac told it, he and his cousin were sitting in a pub in Ballinamore when a group of Black and Tans came in. They came up to the pair and said, "which one of you is John McDermott?" The respondent was immediately strong-armed outside and summarily shot. Mac made his way out the back door. The local parish priest at the Drumleigh church got Mac a second class ticket on a steamer to America. Mac claimed that he escaped the attention of the authorities because they only checked steerage. Any comments, facts to add, or pointers to quality reference sources?

-

I had a shufty at the Last Word portion of the New Scientist website. (Ha! Thanks to you, Chris, I’m the first native Texan ever to utter that initial phrase.) Some of the questions are a bit “out there”, e.g., What would happen to the world if the Earth were hollow below the crust? I hope your question is chosen, but I fear it doesn’t contain enough information. You were faced with some tough choices. As phrased, it is not entirely clear you believe the effect to be specific to, or at least most pronounced on the concertina. On the other hand, if you had made it concertina-specific, most readers would probably say, “Oh, well, I don’t know anything about concertinas.” We’re a little short on hard evidence here. Let me posit some questions for you. (1) I believe someone said concertina reeds were more affected than accordion reeds. Chris, you have both types and a baritone as well. Under what conditions is the effect most pronounced? Is there a specific frequency range where it’s worst? (2) The question of orientation has not quite been addressed to my satisfaction. Chris, you could have Anne sit and play a series of notes on first the side facing the fan, then on the other side. On the English, the notes would thereby be about counterbalanced for pitch. You could also stand nearer the fan than she, and then further away. Does it make a difference? What is the effect of varying the distance you stand from Anne? What is the effect of varying the speed of the fan? (3) Is the interference produced in the concertina, in the air, or in the ear? Some experiments: Record while producing the effect. Turn the fan off. Record the same playing without the fan. Play back the tape. Can you hear the effect on the tape? Can you produce the effect with a tape made without the fan, but played with the fan? This might help determine if the effect is produced by concertina-specific mechanisms or is a purely acoustic phenomenon. It is quite possible the effect might be specific to harmonic balances not reproduced accurately by the taping mechanism, however. Another version of this would be to use headphones and a pickup on the concertina. If the effect is produced “at the concertina”, you should hear it. If the effect is produced as it is transmitted to you, you would not. (4) Determine for sure that Anne’s violin does not produce the effect. Whistle and harmonica data would be useful. Got any brass or wind instruments lying around? (5) Of course, now that you’ve got the recording, get Danny Chapman to do wavelet or Fourier analysis on recordings with and without the fan running. More work than you had in mind? Also, I make no claim I can interpret the evidence were you to collect it.

-

My first acquaintance with the name Wheatstone, like that of some other members, most likely, was in the term “Wheatstone bridge”, more than 30 years before I became aware of concertinas. This page details that and many other products of CW’s inventive mind. It was David Barnert, I believe, who once posted about his invention of the pseudoscope. Many of the books I have been reading lately have left me marvelling at the amazing talents and achievements of the amateur inventor/scientists of the 18th and 19th centuries. Their drive and abilities often seem to have been matched only by their eccentricities.

-

Another Descriptive Word For The Concertina!

Stephen Mills replied to premo's topic in General Concertina Discussion

The antiquated instrument player is our c.netter in Pompano Beach, Florida, Brian Humphrey. You can hear extended clips of this album at the cdbaby website. Brian's playing is not featured as heavily as we would want, but you can hear him on Shenandoah and elsewhere. While you're at cdbaby, check out Grand Picnic's cuts. This is Jody Kruskal's group. I find Galician Waltz and Puff Adder Quickstep especially interesting. I believe I've tracked down the dots to the Galician Waltz, if anyone besides me finds it irresistible. If you're not previously familiar with CDBaby, you'll find lots of good stuff there, with long sample clips and good prices. I have no financial interest (which has been a lifelong problem). -

Review Of Concertina Workshop In East Texas

Stephen Mills replied to Dan Worrall's topic in Public News & Announcements

I will add my observations. Foremost, I would like to thank Dan for organizing this event. It was clearly a lot of work. Well done! Look for a treatment by Dan of the William Kimber style of playing to appear soon. Here’s an ID of the group photo for the curious. We were feeling a little pixelated by the second day. From L to R: Seated: Harold Herrington, Rodney Farr Middle: Maxine Cathey, Nancy Bessent, Mark Gilston Rear: Dan Worrall, Kurt Braun, Stephen Mills, Gary Coover, Jim Bayliss. Roy Janik also attended, but left before the photo. I have been playing for a year and a half, but until this meeting, I had never heard another concertina player play (live). The meeting was a revelation on several fronts. (1) Even in Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana, there are a lot of very good concertina players. The meeting needed more beginning to intermediate players to keep me company. (2) Besides being an entertaining storyteller, Harold Herrington makes a superb concertina. I wasn’t exactly expecting otherwise, but for whatever reasons, Harold doesn’t get the press of the other North American makers. Bob Tedrow’s touring Anglo was in attendance and also had superb tone, action and looks. Roy Janik had his Morse Ceili, but not yet his Carroll. Any Edgley players up for next year? (3) Mark Gilston of Austin was one of the festival scheduled performers and taught an English accompaniment workshop. His English accompaniment style was extraordinary and I found his performance of some haunting Balkan tunes especially superb. (4) If I’m going to try to play with Irish players, I definitely need to get away from the “dots”, other than as a prelude to just learning the tune. A close corollary is that I need to train my ear to a much higher degree. Switching between Anglo and English according to which I prefer for each tune, which is no problem in a relaxed home environment, was a disaster when trying to play a little beyond my comfortable speed. By the time I reprogrammed my fingers, the tune was over. I suppose when you reach a high level of proficiency on both, these problems disappear. (5) If you’re going to Palestine, TX, pronounce it “Pal eh steen” and don’t bite into anything breaded and fried unless you know what you’re doing. It might be fried macaroni-and-cheese, or who knows what else. -

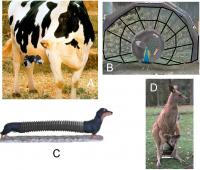

As one of several scientists on c.net, I try to monitor the scientific literature for matters relating to concertinas and concertina-playing. Recently, I had noted a trend among neurobiologists to name newly discovered proteins arbitrarily, much like physicists name quarks “truth”, “beauty,” and so forth. Various synaptic proteins have been named bassoon, oboe, and piccolo, for example. Naturally, I wondered whether there might be a “concertina” protein anywhere in the scientific literature. A quick search uncovered the following abstract, which showed that there was in fact not only a concertina protein, but that the gene that encodes it is also called concertina. This gene encodes a part of the gastrulation process in the fly Drosophila, which involves a process of folding that must give it its name. Following up, I came across an interesting “concertina”-related paper in the scientific literature. Since the paper was rather technical, I found an interview in a more popular-style science magazine. I have copied the most relevant part below. Nature Daily News: Dr. Weizenstein, tell us a little about how you got the idea for these studies. Weizenstein: Walter Gehring and his colleagues created quite a stir in 1995 (abstract) when they showed that implanting the mouse eye gene in Drosophila produces extra eyes in the flies (Figure 1A), and implanting the Drosophila eye gene in mice also produced these “ectopic” eyes in mice. What was surprising was that we had always thought genes encoded specific proteins, so the fly gene would make fly eyes in the mouse and vice versa. It seems instead that they’re what we call “master control genes”. Their protein initiates a program rather than a specific set of structures. So the mouse gene makes fly eyes in the fly and mouse eyes in the mouse, and the fly gene does the same. So we felt that perhaps the result of implanting the concertina gene in other species to make species-specific organs would be interesting. NSD: What did you find? W: Well, we found a profusion of little tiny concertinas growing all over the flies. (See Fig 1B) NSD: Were they real concertinas? Could they make sounds? W: Well, it’s hard to tell. First, you have to play them with micromanipulators. Secondly, A is tuned to 3520 Hz, so they’re pretty hard to hear. NSD. So, what was the next step, Dr. Weizenstein? Next, we tried the squid, because we were already using those for another project. As this article shows, the genetic program seemed to take over the whole organism. The results were disappointing, but actually quite tasty! From there we went on to mammals. Although what we found differed across species, the results were almost always interesting. Look at some of the examples (Figure 2). In some cases, animals repeatedly produced complete concertinas in a kind of “budding off” fashion (A). At other times (B, C), the new ectopic organ was an integral part of the animal and could not be detached. There were also cases of spontaneous regressive mutations that produced deeply disturbing phenotypes, as in panel D. There was much more in this article, but that’s enough about this exciting development for now. I’m off to the Southwest Concertina Workshop in Palestine, TX today, so I will not be available to respond to any comments you might have for a couple of days.