ttonon

-

Posts

359 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Posts posted by ttonon

-

-

Hi Don,

I see I misunderstood your experiment. You propose to use a synthesized tone that has its attack transient chopped off in a recording that is perhaps made with a digital keyboard? This is also very interesting.

Related to this is the complexity of perception of musical tones (Perception of Attack Transients in Musical Tones, chrome-extension://oemmndcbldboiebfnladdacbdfmadadm/https://ccrma.stanford.edu/files/papers/stanm17.pdf). An experiment was done that involved using different musical instruments to play successive notes in a musical composition (klangfarbenmelodie). The musicians had a difficult time playing in fast passages their required note at the exact "time" as written. I think most musicians can appreciate how difficult such a task would be. Yhus, computer music fans decided to take recordings of the separate notes separately, then piece them all together according to the written composition. An interesting problem occurred upon playback. According to listeners, the separate notes were not placed into the master recording at the right times. The rhythm was way off. It turns out that our perception of attack differs greatly when perceiving notes from different instruments, as I allude to in my other post, regarding the definition of PAT. Thus, PAT needed to be considered when computerizing the sound file. As explained in the above reference, a relative PAT (RPAT) can be incorporated, in which any instrument in the orchestra could be used as a reference. So the time difference between the physical occurrence of a pressure pulse of a violin and its PAT can be referenced to a known PAT of another instrument, and this RPAT can be used for any note of a violin. In the reference, there are too many other complications presented than I could present here.

If your recording contains only the truncated synthesized notes you generate, there should be no complications involving PAT. However, if you try making your recording with a background of other instruments playing and interlacing with your melody, you may run into problems of rhythm. Incidentally, it occurs to me that any musician familiar with the sound of his/her instrument must have an intuitive feel for the PAT of the notes played. here may be significant variation of the PAT for different ranges of the same instrument, and maybe some musicians are aware of that while playing, or the adjustments may be unconscious.

I still encourage you to do the experiment.

Best regards,

Tom

-

Hi Alex,

Sorry I misinterpreted. That’s an interesting observation and consistent I think with what I’m proposing. The leakage means a couple things. First, it reduces the maximum static pressure that the tongue could experience, because the leakage flow causes a slightly larger pressure under the tongue than the static pressure under the reed. The max pressure difference is thus slightly less than the full bellows pressure (either + or -). It's thus harder for static bellows pressure to hold the tip in the slot (to choke). A smaller offset therefore increases the effect of the reduced static pressure. Second, leakage probably aids the formation, or persistence, of turbulent eddies in the wake of the tongue because of enhanced air flow. The tip can now rest closer to the slot before the valve effect cuts off the airflow necessary for the eddies.

I should correct myself here. According to the usual rules in the Physics community, I have an hypothesis with this eddy idea, not a theory. It’s not yet a theory until substantial experimental evidence has supported it. But since hypotheses that satisfactorily explain heretofore unexplained phenomena, maybe we’re on the road to a theory!

Thanks for your diligent reed experiment, for which I commend you, and I think it demonstrates remarkable behavior. According to my hypothesis, the explanation why a small bellows pressure can start a tongue with small offset, yet a large bellows pressure will choke the tongue in the slot is that, with small pressure the static deflection it produces in the tongue is less (linearly so with pressure), and a wake is allowed to persist with the formation of periodic eddies. Then, yada yada, the tongue initiates vibration by the resulting periodic forces. With high pressure, the tongue is quickly bent down into the slot, not allowing enough time for resonant response to build to sufficient amplitude in order to initiate vibration. It always takes time for resonant amplitude to build, because of inertia in the structure and in the surrounding air.

Your subsequent observation is very enticing. It’s easy to see why the sloppier fit will cause louder hiss, but the fact that you observe that both reeds spontaneously started while keeping the choking pressure applied after a few seconds puzzles me. How closely did you observe the very start of speaking? Did the tongues first come out of the slot, then you heard the low tone, or did you hear the low tone while they were still inside the slot? Were the tongues well within the slot or very close, just outside it?

If you heard the low tone while the tongues were in the slot, then apparently there was some unsteady turbulent effect going on, which is what puzzles me. The flow through the small gap between tongue and slot wall, with constant Pb, is steady and no doubt laminar, because the Re there will be very small (based on the width of the gap). Once the flow is through the gap, and since the flow is steady, a jet forms upon exit from the gap. I would expect this jet to be laminar as well. After a distance, a laminar jet can turn into a turbulent one, and maybe there is the key. Such a distance is a certain number of jet widths, and since this gap is in the thousandths of an inch, it’s possible that the jet is turbulent by the time it exits the slot. Whatever, with turbulence, there’s the possibility of periodic eddies. The presence of the slot wall on one side of the jet does complicate the mechanism. But I’m guessing here and I’ll have to think more on it, with maybe more input from you. The key here may be exactly where the tongue is when you hear the very first instance of tonal sound.

Best regards,

Tom

-

Hi Don,

Thanks for your interesting comments and suggestions. I never thought to omit the start transient from all the notes of a musical recording as you suggest and it would be a very interesting experiment. If you’re willing to do the work, I guess you will find some interesting results.

Other researchers have done experiments in order to evaluate the importance of start transients (although in accepted terminology we should replace that term with “attack”). For instance, playing a musical tone from a piano or guitar backwards in time produces incomprehensible sounds. We rarely experience musical tones without the associated attack, which is remarkably important to our entire perception of tone. In fact, as humans are likely to constantly find complexity in Nature, in the literature you find the terms “perceptual attack time,” as opposed to “perceptual onset time,” PAT and POT. PAT is the perceived time it takes for the attack to be completed, and POT is the perceived time when the onset of the tone begins. Of course, these are different from the time of the actual physical evidence for the start of the tone; i.e., a pressure pulse, or the time it takes for the actual physical duration of the transient, as measured by Fourier wave forms. Usually, the fundamental and low overtones are established first, with higher overtones establishing later. At some moment our brains tell us that the tone started, even though the higher harmonics of some musical tones are still building, sometimes taking up to a second or so to complete. And then, in some tones, transients never stop; i.e., there’s a distinction between a steady tone and a constant tone. We don’t experience constant tones. We call a tone steady when it doesn’t appear to change in time; however, it does change with most any musical instrument, in minute ways by which various overtones keep adjusting.

I hope you don’t think I’m digressing too far here. I sense that many members here are interested in these perhaps esoteric subjects, and if anything else, it all describes the enormous complexity behind the operation and perception of the free reed tone, even though it’s often assumed to be a simple minded thing.

But more direct to your comments, I quote the abstract of the paper, “Attacks and Releases as Factors in Instrument Identification,” Charles A. Elliott, Journal of Research in Music Education, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Spring, 1975), pp. 35-40, below.

Abstract

Identification of musical instruments according to their individual timbres was the focus of this study. It was theorized that the attack and release of a tone could be a factor in identifying specific instruments. For testing purposes, a two-part master tape recording was prepared--part A containing 18 randomized instrumental tones with attacks and releases spliced out, part B containing 18 unaltered, randomized tones sounded by the same instruments as in part A. A total of 57 graduate music students served as subjects. Results showed that in part A (attacks and releases removed), only three instruments--Bb clarinet, oboe, and trumpet--were correctly identified a significant number of times; in part B (unaltered tones), all instruments except the cello were correctly identified a significant number of times. For all participants, the mean score was significantly higher on part B than on part A. Thus, it was concluded that attacks and releases may well be influential factors in differentiating between and identifying specific instrumental tones.

Notice in the above that the “release” of the note can be an important musical clue, since the manner in which musical tones terminate can be complex, especially when considering perception. The experiment doesn’t seem to separate attack from release, though other experiments yield similar results only for attacks.

The experiment you suggest I think carries this idea to the ultimate. Usually, experiments like the above involve the presentation of long duration, single note audio to a listener, and there, the mind is less cluttered with all the other stuff in music performance. There are of course other experiments, and one I recall concluded that with many fast, short notes being played, the listener is relying virtually only on the attack, and not the steady tone for identification of different instruments.

Your suggestion for a magnetically enhanced attack is interesting, though such initiation of vibration cannot be as fast as a direct mechanical stimulus. Unless maybe if you borrow one of those superconductive magnets they use at LHC, but such an apparatus could be dangerous for the player and anyone else in the room!

Best regards,

Tom

-

Hi Ken, thanks for the interesting comments on your early experiences. If you're from Indiana, I'd guess that your dad was stationed at Purdue University, a very well known center for aerospace/aeronautical education. My best wishes for your mom, and thanks much for the dramatic picture of a von Karman vortex street.

Alex, thanks for your comments. I believe the theory does support an interpretation consistent with your observations. Larger offset means that the spring of the tongue can resist being trapped inside the slot with higher bellows pressure, up to a limit, I suppose. Also, with larger offset, the theory predicts higher starting pressure, again because of the springiness in the tongue.

Have you observed for small offsets that when the reed is choked, the tongue sits motionless in the slot? (I guess so, since this is what we mean by choking.)

Best regards,

Tom

-

I'd like to comment further on the topic I discussed in the next to last paragraph of my post above, concerning the need to choose a (minimum) start pressure, Ps.

Minimum and maximum start pressures, Ps:

It's possible for the tip offset, a, to be so large that the tongue will not speak. This would occur if the eddy induced vibration amplitude of the tongue tip cannot grow as large as a. With any vibration, at resonance, the vibration amplitude is fixed by the dissipation in the system, the energy supplied by the external periodic force being then balanced by the dissipation in the system. In my own experience, it's also possible for the offset to be too small for the tongue to speak. I've seen the tip trapped in the slot entrance, in the presence of bellows pressure. Such a fact gives credence to the basic assumption here; i.e., that an unsteady turbulence in the wake of the air flow passing over the tip is required to initiate the tongue to vibrate, then speak. Because of this fact a maximum start pressure Ps should be that required to statically deflect tongue so that the tip lies just within the slot entrance. Experimentally, we can find a minimum start pressure by pushing the tip into the slot with a sharp edge, at a given bellows pressure. Then let go of the tip and see what happens, keeping the same pressure applied. Try this for different pressures, starting from very small. With the minimum pressure, I envision that upon release the tip will come out of the slot (because the pressure is less than the Ps max), but then start vibrating because of turbulence, and quickly start speaking. We have thus found the minimum start pressure that induces speaking, for that particular value of tip offset. This is a simple experiment, which I plan to do, and I'm interested in the difference between the minimum and maximum values for Ps. My guess is that the difference should increase as the tip offset increases, up to the point where the tip offset is too large to allow speaking, as explained above.

-

My thoughts have swung to free reeds again and it occurred to me that there may be an interesting way to theoretically determine an optimum static offset distance for the quiescent tongue. As most of us here know, the offset is the distance the tip of the motionless tongue stands away from the plane of entrance to the slot below. I’m sure some of the makers here ask, what’s the need for such a theory? There isn’t really; makers get along well without it. But for those of us fascinated by the operational details of the free reed, such a theory can illustrate more of the intricate physical principles by which our musical source works.

My interest in this topic was piqued during a discussion on this forum when several of us were postulating just how the tongue starts vibrating. Someone posted slow motion videos of the starting tongue and what struck me was that the first sign of motion of the tongue tip was a minute vibration that slowly grew in amplitude, until the tip entered the plane of the slot opening. At that instant, the amplitude of vibration increased very rapidly.

The western free reed has a notoriously slow start transient – the time it takes from the application of pressure difference to the moment in which the musical tone can be considered to be fully developed. In fact, there was a period during the 20th Century when free reed organ pipes were in disfavor, precisely because of that. Typically it takes many tens of milliseconds for the transient. I myself think this feature is a hindrance to the bellows driven version in some musical settings. Perhaps it can be improved by somehow linking the key to an arm that flips the tongue the moment the key is pressed. Such a mechanism might eliminate the sluggish start period of time in which the tip is building up the amplitude of its vibration outside the slot. Apart from the time delay, a short, sudden start transient usually adds color and character to the entire musical tone. When we hear the fully developed tones of many musical instruments, when the start transient has been digitally removed, we can’t distinguish them, for instance a violin from a free reed, or even a beating reed, such as a saxophone, or a string sound from a guitar or piano. A crisp start transient also helps distinguish a musical instrument from other instruments in an ensemble, and it helps distinguish one note from the instrument from another note from the same instrument. The piano is a marvelous instrument with a wonderful, percussive start transit. In my opinion, it’s why it works so well in Jazz, hammering out complicated chords in which individual notes can be well distinguished, much unlike the accordion, or English concertina. This is an interesting, though large topic, and let’s get back to nudging the tongue in order to start speaking.

The fact is, when the tongue is in that entrance plane, the static pressure force on the tongue is maximum. Assuming that we have a perfectly made reed with a tongue that perfectly fits its slot, this maximum pressure force is equal to the (static) bellows pressure difference times the footprint area of the tongue. There are no other static pressure forces in the system that can be larger than this, because before that moment, with the tongue still vibrating outside the slot, the static pressure in the air flowing around the sides of the tongue, under the tongue and into the slot is everywhere a little above the static pressure on the underside of the slot. It’s when the static pressure under the tongue equals the static pressure below the plate that the maximum bellows static pressure force is experienced by the tongue, and that occurs when the tongue completely covers the slot, blocking all air flow. This explains the observed very rapid increase in vibration amplitude. At that moment, the mechanism for nudging the tongue changes from eddy induced vibration (explained below) to a more direct and much larger pressure force that acts uniformly over the total top area of the tongue. At that moment of tongue coverage, we can write, during push of the bellows and a rectangular tongue, J = (Pb – Pa)*L*W, where J is total pressure force distributed uniformly over the tongue, Pb is bellows pressure, Pa is atmospheric pressure, L is tongue length, and W is tongue width.

The above static pressure description is really only secondary to the offset theory I’d like to present here. However, it prepares ground for good visualization of the physics.

My other key observation of the slow motion video start of tongue vibration was that the initial, small amplitude vibration of the tongue – before being forced into the slot – was obviously (to me) the result of vortex induced vibration (VIV), or at least periodic eddy induced vibration. VIV is an extremely well studied phenomenon, being of interest to architects and aeronautical engineers concerned for the potential damage such a process can cause to large, expensive manmade structures such as bridges, buildings, transmission towers and lines, etc. and aircraft, rockets, and the like. Most of us know about the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows bridge, only four months after it was built over Puget Sound, Washington, in which self-induced vibrations shook the bridge to pieces in only a 40 mph wind, causing the death of a pet dog in a car, both of which were never recovered in the 200 foot deep water below. For many such structures, VIV is bad; for free reeds, it’s good, because your concertina can’t speak without it (I think).

Two most notable individuals associated with understanding vortex formation are Vincenc Strouhal, a Czech, and Theodore Von Karman, a Hungarian-American. Strouhal studied the inherently unsteady process of vortex formation in the wake of bluff bodies, arriving at well-known correlations between Strouhal Number and Reynolds Number. Von Karman shed (no pun) much light on what are called “vortex streets,” which are periodic formations of vortices in the wake of a blunt body in a fluid flow stream. Depending upon the Reynold’s Number (Re), or for a given geometry and fluid, the fluid velocity, turbulent eddys in the wake of the body form various patterns in space and time. A large regime for Re produces von Karman vortex streets, wherein vortices appear alternatively on both sides of the object, becoming regularly spaced and periodic in time. These periodic structures in turn cause periodic forces on the structures, and when these periodic forces couple to the natural vibration modes of the structures, large amplitudes of periodic structural motions can occur, called “galloping,” or “flutter.” Such vortex streets encompass a tremendous range of scale, ranging from geological scales observable from satellites in the wake of Eastern Atlantic Ocean islands, down to individual blades of grass, and down to our tiniest free reed tongues. They probably also occur in outer space. Notice here that the wake of the free reed tongue doesn’t extend very far (taking “far” to mean in comparison to W) before any turbulent eddies approach/hit the slot. I’m assuming the eddy interaction about the immediate region of the tongue surface is key and that perhaps the slot allows eddies to pass through easily enough not to greatly disturb the picture.

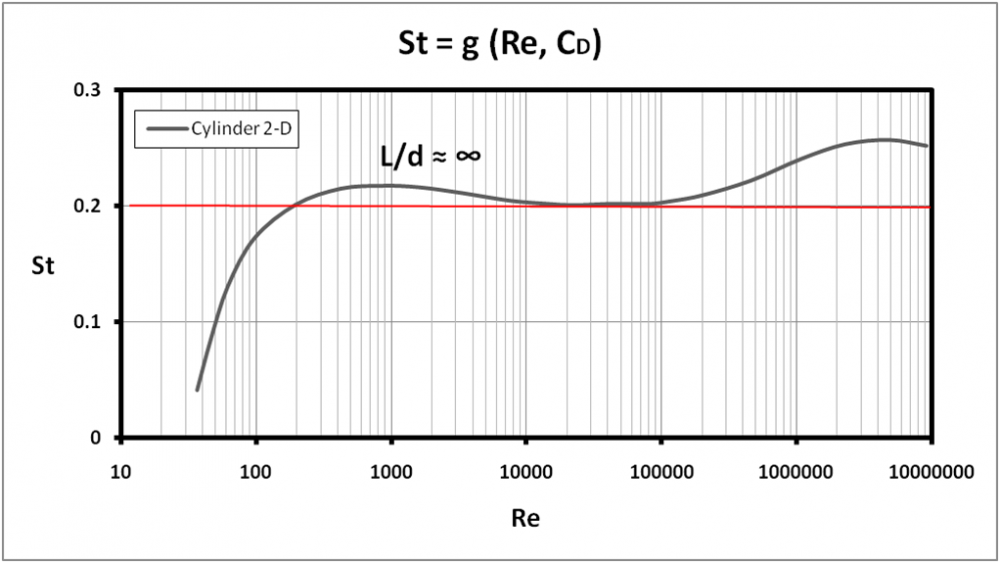

The attached figure shows the St vs Re plot attained by Strouhal, around the year 1878. This is a cleaned up plot, eliminating the large number of data points and error spread bars. We make use of this information in our Free Reed Tongue Tip Offset theory.

The Strouhal Number is given by St = F*W/V, where F is the frequency of eddy formation, W is tongue tip width, and V is air velocity past the tip. Notice that it’s the ratio of two times, the time an air particle moving past the tip remains in the vicinity of the tip (W/V) and the period time of vortex formation, since F = 1/T, where T is the period. This ratio has physical meaning. For instance, if the time an air particle spends near the tip is small compared to the period, its view, or experience of a forming vortex will be as though the vortex is stationary. Unless it’s trapped in the whirl of the vortex. The vortex, being a whirlpool just like a hurricane, experiences very fast tangentially moving air, while the entire structure moves at a relatively slow rate (e.g., the “eye”). Such a picture explains why St values in the figure are not much above 0.2, even though the motion is unsteady. Normally, such low time ratios in periodic fluid motion would lead to a conclusion that individual fluid packets experience very little unsteady (time dependent) changes, allowing one to view the overall motion as “quasi-steady.” But in this case, the washing machine regurgitation of the packets in the vortex - like Hurricane Harvey did to Houston - keeps the packets in the region of unsteadiness, leading to the conclusion that vortex formation is inherently unsteady. Without vortices, air flow produced by constant pressure difference would cause steady flow. Hence, vortices convert a steady flow into a periodic unsteady flow, which is necessary to start the unsteady vibration of the tongue.

The Reynold’s Number is given by Re = W*V/nu, where nu is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid. As I understand it, this expression was first introduced by George Stokes, an Irishman, but it was made popular by Osborne Reynolds, another Irishman. The Reynolds Number is an extremely important parameter in fluid flow, showing up in all kinds of disparate flow conditions. It is usually interpreted as a ratio of forces, inertial forces to viscous forces, and I recommend that interested people check out the wiki page (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reynolds_number) that explains the progression from these forces to the expression above. This page is useful also because it shows a cartoon video on the vortex street behind a bluff body in fluid flow. It's a beautiful play produced by Nature, and from it, one cannot but help not to make the connection between vortices and periodic structural forces. (This is an example of the www at its finest, and incidentally, wiki asks all of its users for a measly $3 donation per year.)

With that background, the gist of the Free Reed Tongue Tip Offset Theory is to first make two important assumptions. 1) the minimum bellows pressure to start the eddies is that static pressure that will hold the tongue tip into the entrance plane of the slot. 2) the dissipation (friction) in the system is small enough to allow a very sharp and pronounced resonance when the tongue is excited by an external periodic force very close to its natural frequency. That last complicated sentence can be greatly simplified by stating that a “high Q” is assumed. Anyone who has studied vibrations or electric circuits should know what that means.

Physically speaking, what we are doing here is to assume that, in order to start speaking, the tongue needs to be excited by a periodic fluid force that is near its (first mode) resonance frequency, and that periodic force is the force supplied by formation of periodic eddies in the wake of the air flow passing over the tongue tip. When those frequencies match, we have excitation. Strictly speaking, we are not even assuming a vortex street. We are only using the data from Strouhal, in which he has correlated discernible periodic wake forces, as expressed by F in his expression for St (above). We know that, for Re from about 47 to many thousands, as in the case with free reeds, vortex streets are the most likely outcome, but that’s an added understanding to the starting process details.

Continuing, one then looks up the Young’s Modulus (E) and bulk density (rho) for the tongue material, decides on the geometry of the tongue, using W, L, and t, the tongue thickness, and assumes a starting value for a, the tip offset. The rectangular cross area moment of inertia is calculated as I = W*t^3/12.

Assumption (1) then allows calculation of the start pressure difference Ps (push or pull of the bellows is inconsequential) in terms of the assumed a and geometry, using a well-known beam formula for a cantilever, fixed at one end, free at the other (where the tip is), and uniformly loaded (as in the case here, with a constant pressure difference). The formula is Ps = a*E*I/(W*L^4).

From the calculated start pressure, Ps, one calculates the resulting air velocity for the air moving about the tongue tip, as follows: V = (2*Ps/rho)^0.5. This air flow of course occurs before the tongue covers the slot, and it’s obtained from energy considerations (Bernoulli), not dependent on the particular geometries, passages, and streamlines.

Next, calculate the Reynolds Number: Re = W*V/nu

Here, we use Strouhal’s correlation in the attached figure, between Strouhal Number, St, and Reynolds Number, Re. The fact that it’s in graphical form breaks complete automation of the calculation. I did make curve fits for this correlation, but I used Excel, and there I’m limited in the number of functional forms. Notice that the graph is a semi-log plot, so the polynomial fits offered cannot cover the entire range of Re. I thus split the graph into three fits, all using a 6th order polynomial. I will return to this shortly.

Once we find the appropriate Strouhal Number value for the Reynolds Number calculated above, we can calculate the frequency of periodic eddy formation from: F = St*V/W, which is derived from the definition of St, above.

With F now calculated, one compares this value to the actual vibration frequency of the tongue. If the calculated F and the actual frequency differ too much, we then assume another offset, a, and redo the calculation until we get reasonable agreement. Physically, this comparison completes the application of the model, which states that the starting eddy frequency is very near the actual vibration frequency.

Returning to the graph issue, I have put in an Excel spreadsheet the entire calculation for a. There’s an input section (material properties, geometry, etc.), a calculated parameter section (I, Ps, V, Re, etc.), a logic (decision) section in which the user selects the proper curve fit for the calculated Re with a simple click, and a final comparative section for the two frequencies.

I would gladly email this spreadsheet to anyone who’d like it. A small request I make is that anyone who receives it to please not share it with others, because I’d like to know who the interested people are. Or, if you do send it to someone, please let me know who it is. For that, I thank you. Though regardless, I won’t contact my lawyer over it.

As a finer point of discussion, the two assumptions listed above are perhaps a bit contradictory. The second requires a large resonance response, yet the first chooses a static start pressure, Ps, able to statically deflect the tip an amount equal to the offset, a. Considering the fact that any mechanical resonant system acted upon by a periodic force produces vibration amplitudes much larger than the amplitude of deflection that force would produce in a strictly static process, one might suspect that the calculated Ps is far larger than the true Ps. But I think it’s more complicated than that. First off, there is no real Ps operating on the system. It’s a fictitious quantity necessary to estimate a start air flow velocity, and since pressure is the only mechanism here to cause air flow, we look for the minimum pressure that can be defined by the given parameters. The actual external periodic force on the tongue that causes motion is that due to the dynamics of eddy formation. This force is different from a Ps pressure force. The eddy dynamics are of course ultimately the result of the applied static bellows pressure, Pb, but there isn’t a one-to-one identification. For me, at least now, I think the idea may give decent results. Of course, we can add complexity to the model by defining a modified start pressure, Ps’ = k*Ps, where Ps is as before and k is some number less than unity that would have to be inputted. I’d be surprised if anyone would be interested enough in this modification to try it, because it means for the maker to keep track of how well the model works for different assumed values of k. I clarify this for purposes of completeness.

From calculations, it seems this model predicts at least realistic values for a, though I plan to investigate it experimentally. Trouble is that my workshops are a mess now, in the middle of major clean up. My guess is that makers – like myself – are so familiar with setting a value for a that it’s done almost by second nature, with simple start trials to check out the setting. But I’m not a maker, and if there does appear that such a theory can be useful in any aspect of this chore, I’d appreciate knowing about it. For me, it was just fun enough putting the pieces together. It gave me a better physical feel for underlying physics, and as far as I know, it’s entirely my own. For instance, I have not come across any hint of it in academic literature on acoustics and vibration.

Best regards,

Tom

www.bluesbox.biz

-

1

1

-

-

Hi Chris,

Excellent!

I always hold out that some other academic type might join these discussions, and indeed, I would celebrate it. In fact, I know (of) a few, and I might drop them a suggestion. I have already invited Jim Cottingham, though I haven't gotten feedback on it, and I fully accept that they might not have too much interest. Anyway, that's the reason I sometimes stick in what I think are relative details suited for us academic types.

Best regards,

Tom

-

Hi Chris,I suppose we have the usual interaction between a theoretician and an experimentalist. A theoretician might propose an experiment, but the experimentalist sees many practical issues that complicate the issue. This has occurred a lot in acoustics, and as an example, I’m sure you know of the attempts to decide the question whether vibrations in the body of a flute affect its acoustics. A suggestion for experimental insight is to build a metal flute and a wooden flute and see if the sounds are the same, and if they are, since the metal vibrations would be different than the wood vibrations, it suggests that body vibrations are not too important. The experimental difficulty of course is to build both metal and wood flutes to the same dimensions, which is not easy to do. But this is a digression.So while the test would need to be simple in order to get done can I suggest the clearance between tongue and frame would need to be consistent across both examples?

I would say yes, when we are interested in timbre. As I mention above, it's probably not as critical if we were only interested in duplicating pitch, but this is basically a guess on my part.

does banging it with a hammer to work harden it only create a zone of surface hardness? What happens when you file it to create a profile, does it lose its hardness on the top? All of the brass I have here is "free machining", ie. includes a small percentage of lead. Can this be used? Does anyone have a working comparative knowledge of steel and brass profiles? Would brass and steel deliver the same pitch for the same physical profile and length and width dimensions? So many questions...Since the entire mass of the brass will flow, banging it with a hammer will work harden the material throughout, and filing it will not reduce the bulk hardness. “Free machining” brass should work, and I think most any type of brass would work. Most all brass types come in three tempers: annealed (after heating and slow cooling), half hard, and full hard. Keep in mind that hardness does not affect Young's Modulus, but does affect ultimate strength. For the same length, a steel tongue should have the same pitch as a brass tongue that is 1.41 times thicker (as I calculated above). For a profiled tongue, the profiles in the different materials should be the same, percent wise.If we are talking about using brass on its own merits, as opposed to an investigation into the reasons why different tongue materials sound differently, there are other practical considerations, and we touched on these in discussions on this news group years ago. I refer to two such threads:Why Does Brass Sound Different Than Steel?Why do Brass Tongues Break?In the first of these, we discuss why brass tongues may sound different than steel tongues, bringing up the idea of tongue velocity and its effect on higher acoustic overtones.In the second of these, we point out the concept of endurance limit for cycling stress in metals and reason that maximum stresses in brass need to be reduced because of its relatively low tolerance for repeated stress. One way to reduce stresses is to reduce the length of the tongue.With both these discussions we see good reasons why brass tongues should play at lower volume, as David Elliot has pointed out in this thread, compared to steel tongues. I haven’t yet digested again all the posts in these extensive threads, but will probably find it necessary to do so as this investigation proceeds.Hopefully, the complete solution of the fluid dynamical model of the vibrating free reed - as I’m pursuing according to the method I explained above - will provide the answers to most of the questions we have been asking. -

Hi Johann,

Let's take the examples of steel and brass. Here's the suggestion:

[E/Rho]B x (aB)2 = [E/Rho]S x (aS)2

aB = [ (E/Rho)S / (E/Rho)B ]1/2 x aS

aB = (2)1/2 x aS

aB = 1.4 x aS

Thus, make the brass tongue thickness 1.4 times that of the steel tongue, and the tongue lengths, L, the same for both materials. This should guarantee that the modal frequencies of vibration will be the same for both tongues. And again, this should not depend upon how well the complete reed assembly is made. Concerning acoustic sound (timbre), we will have to investigate further into what geometries can be used to impart the same timbre, if possible. But let's go step by step.

Notice that the above result probably means that the brass tongue will be stiffer to the feel than will be the steel tongue, or in other words, the spring constant is higher for the brass tongue. This must be because the brass tongue, with higher density, will also be more massive than the steel tongue. The stiffness increases as the fourth power of the thickness (really the moment of inertia), whereas the mass increases only linearly with the thickness. Thus the effect of stiffness overcomes the effect of mass increase very quickly. The higher stiffness for the heavier tongue is needed in order to keep the mode frequencies the same for the two tongues.

Best regards,

Tom

-

I apologize for this delayed response to the many interesting comments in this thread I started. I’ve been going out of town and tending to important issues. For those who don’t know, I’m in Complete Response for Multiple Myeloma, a cancer of the plasma cells in the bone marrow. I have medical treatments (infusions) two days of every other week, and they give me headaches and hangover, but I’m not complaining, it’s not too bad. If by chance, anyone else in the group is going through the same thing, I invite you to contact me privately and we can compare notes, even though this disease is extremely variable.

Now being able to provide a more energetic description, I must first state clearly that the suggestion I proposed in the OP is really only the simplest theoretical step in trying to understand why different tongue materials might produce different acoustic effects, and I want to correct a sentence in the “Quote” part of that post, which was a misstatement:

According to these theoretical considerations, both tongues should produce the same

acoustic soundvibration: fundamental plus overtones.The Euler-Bernoulli wave equation for a vibrating bar is the simplest formulation for such behavior, and it is considered very accurate when rotational inertia and translational shear can be neglected, and that is the case if the thickness of the bar is not too great and the vibrations contain only small angles, which often occurs with free reed tongue vibration.

Attached is a .docx file that gives the E-B bar equation and the Timoshenko bar equation. I was not permitted to upload this file. Anyone?

Shown is the simplest form for the E-B bar equation, which does not include a forcing function (external force, such as a bellow’s pressure), nor aerodynamic drag (friction) terms. Mathematically, it is called a non-dissipative (frictionless), homogeneous formulation, and the utility of it is that it (along with its boundary conditions) provides the eigenfunctions for any type of bar vibration consistent with its underlying simplifications. In other words, the complete solution when you do include a forcing function with friction (the complete formulation) is made up of these same eigenfunctions, which give the axial dependence of the shape of the bar (its curve). The time dependence of the vibration in this complete case is then determined by the time dependency of the forcing function with the complete formulation.

Thus, the simple suggestion in my OP will reliably predict accurate frequencies and general axial beam shapes for the fundamental and overtones that are experienced in actual operation (with dissipation and bellows pressure). And it does not depend much on how accurately the tongue and slot (entire reed) is made. However, it cannot give a complete description of the oscillations in air pressure (the acoustic sound) that the vibrating tongue produces. Let’s focus now on the acoustic sound, which is our prime interest.

In order to predict a complete description of the acoustic sound of the reed, we need to know how the vibrating tongue motion translates to oscillatory air motion, and this air motion needs to be understood in the near field (close to the vibrating tongue) and the far field (after the sound waves move to a region away from the reed – say to a region that is more than about ten tongue lengths away, which is the sound we hear). With a complete formulation, we will get some information on the acoustic near field, and here, we may be in luck, at least in so far as making conclusions about how different tongue materials might compare in their acoustic sound (volume and frequency spectrum, or timbre). These conclusions would be enabled because of the addition of a forcing function and dissipation terms into the E-B bar equation, and scrutinizing those terms. It’s the same way I suggested in my OP, only now we have more terms in the equation. The boundary conditions (B.C.) remain the same in this complete formulation (fixed at one end, free at the other).

In order to accurately determine what these terms are, we need to develop an accurate physical model for the tongue motion, and how this motion interacts with air movement. I developed such a model after I was invited to deliver a paper at the Acoustical Society of America 2017 meeting this last Dec 4 – 8 in New Orleans. I delivered the paper, with the published Abstract:

http://asa.scitation.org/doi/abs/10.1121/1.5014394

New Orleans was fun, and this paper is a work in progress. I have completed the physical model and have conjured a mathematical method of solution for the resulting governing equation and B.C. I now have to finish the formal solution - which at this point, is mostly a lot of Algebra - and to perform calculations and graphical results, check agreement with experiment, etc. But because of further travel plans out of the country, work on this project will be put off for more than a month.

I’m explaining all this in the hopes that I can convince a reed maker to first take up the simplest suggestion in my OP. By Spring, I should have completed the analysis and could hopefully make some statements about what geometry would be required to cajole two tongues of different material to not only vibrate with the same frequency and have the same overtones, but also to produce the same acoustic sound, if possible. It may not be possible. And of course, it may not be possible to find such simplistic generalizations from only this study, in which case, we would have to rely on an acoustical analysis of the air sound field. But let’s not yet give up hope on the simplest approaches first.

I wasn’t sure how to present all this, and I hope I haven’t confused things with my attempted explanation here. I’m glad to answer any questions, if I can. In the coming days, I plan to respond to the comments by others in this thread.

Best regards,

Tom

-

Greetings fellow free reed enthusiasts,

In another thread, I made the following suggestion, and perhaps it's worth including it in its own thread.

As an aside, this result suggests a very interesting experiment that concertina reed makers might want to try. Make two different tongues of different materials (say steel and brass), with constant cross sectional area and having the same length and the same parameter E*(a^2)/Rho. According to these theoretical considerations, both tongues should produce the same acoustic sound: fundamental plus overtones. My feeling is that, if this conclusion can be experimentally verified, our understanding of the free reed would be significantly increased.

In the above, E is Young's Modulus, a is tongue thickness, and Rho is material density. The simplest example would be a tongue with constant cross section vs. axial length: no taper and no profiling. I believe the criteria here apply also to cases of taper and profiling, as long as their axial dependencies are the same for both tongues, but I'd first like to look at the corresponding solution to the wave equation before asserting that here.

Best regards,

Tom

www.bluesbox.biz

-

Hi Umut,

I think I have a much better idea on what you're asking, and let me offer the following.

In general, metals have the lowest Damping Capacity of all materials, and of these, from the information I sent you, Aluminum appears to have the lowest. Thus, I would recommend you try making a gong out of Aluminum. Do you know of other people trying Aluminum gongs? Perhaps a serious problem with Aluminum might be its relatively low endurance limit. In order to evaluate this, you need to estimate the maximum internal stresses that the metal would experience as a gong, and at what frequencies those stresses occur. For this, you can consult the circular plate vibration solution that Morse has in his book (as I explained above). With that information, you should be able to estimate the life time of the gong. Important also is the fact that there are many different kinds of Aluminum alloy, each with its own Damping Capacity and endurance limit. Hopefully, you'd get lucky and find a good enough alloy that's affordable. Traditional gongs and bells aren't made out of Aluminum because this metal wasn't widely available until this last century. When it was discovered about 200 years ago, it cost more than gold, and it wasn't cheaply produced until only the last century. Copper and bronze however have been utilitarian for a few thousand years now.

It's not correct to conclude that the low tabulated Damping Capacity for glass fiber ( 0.1) means that you can use it in a composite and it will increase the Damping Capacity of the composite. This value must be valid for a single fiber stretched longitudinally, and not for broken fibers immersed in a matrix.

Putting any additive (fibers, nanotubes, powders, etc.) into a material will most likely increase the Damping Capacity over that of the material alone. This is because there will always be some relative motion between the additive and the matrix, and this rubbing produces dissipation of energy, heating the material.

Making a gong out of separate components should be avoided, because again, there will be relative motion between these components, causing vibrational energy losses. The gong should be made out of one homogeneous material (e.g., Aluminum, or an alloy of Aluminum).

I haven't seen much data, but my guess is that thermoplastics, thermosets, and other polymers have more Damping Capacity than metals, because they have long molecular chains that easily distort, using up vibrational energy. If you do find any will lower levels, please let me know.

Glass bells and gongs are fairly common in small sizes. Wind chimes, wine glasses, the glass harmonica (the one invented by Benjamin Franklin), etc. all prove that solid glass can be a resonant material. But again, I think that a solid glass gong would perform best, and in order to make one, I'd first talk to a glass worker.

Best regards,

Tom

-

1

1

-

-

Hi Umut,

How one can build a glass reinforced plastic prestressed.

A few ideas:

Solid Glass:

Has anyone tried to make a solid "tempered" glass gong? You can try casting a circular molten glass shape, then find a way to cool it rapidly over the entire outside surface, before it can cool throughout the interior. Then let it cool more slowly in the interior. This is basically how they make tempered glass, which has the outer surfaces in compressive stress and the inner regions in tensile stress.

Thermoplastic:

Perhaps a thermoplastic (not epoxy) dome can be cooled in a similar way, resulting in its outer surface in compression and its inner regions in tension?

Thermoset plastic:

For epoxy, since the cure rate of epoxy increases with temperature, you might first cast the epoxy in a circular shape, then when it becomes firm enough, heat all the outer surfaces uniformly with infra-red (radiative) heaters. This will cure the outer surfaces first. Keep heating (maybe with an adjustment on heat flux) until the inner regions become cured.

Best regards,

Tom

-

I'm constantly amazed by the progress being made by enthusiastic researchers, who keep coming up with new possibilities in most any field of science, medicine, and technology - possibilities that we couldn't conceive of only a couple decades ago. I just hope we can turn away from our destructive tendencies enough so that these ideas can come to fruition. Yes indeed, now is the time to start out on a career that can immerse you in such exciting developments - at least for us privileged enough to benefit from the education and wealth that provide the basis for such a fortunate career.

Best regards,

Tom

-

Hi Umut,

At this point, I'm not sure what you want to do. Do you want to make a gong of concrete, or do you want to make a gong with a minimum amount of dissipation, so that it has the longest ring?

If the latter, you might find this comprehensive materials survey interesting:

Documentation of damping capacity of metallic, ceramic and metal-matrix composite materials:

https://faculty.engr.utexas.edu/sites/default/files/jmatersci_v28n9y1993p2395.pdf

Best regards,

Tom

-

Hi Umut,

In this thread, we are talking about two kinds of vibrating objects – free reed tongues (also called bars) and gongs (also called plates) - composed of two kinds of materials – metals and concrete.

I believe your main interest concerns the vibration of concrete gongs, and perhaps your interest in metallic bars is in order to help you get an understanding of concrete gongs.

I point out these differences because each of these special cases requires different theoretical treatment, and one can error by confusing each of them.

My friends asks me if the modulus density ratio is the same , the fundemental frequency is the same. They asks me what will be the harmonics and their sustain for each different.

I read your post on concertina reeds and as fas as I understand , you defend every characteristics would be the same.

Is it true ?

Yes, in the case of vibrating bars that are homogeneous (have the same material and cross sectional area throughout their lengths), as described by the Euler-Bernoulli governing equation (which works well for the vibration of tongues of the Free Reed), if the ratios E/Rho and the geometries are the same.

As a matter of fact, in these cases, the Euler-Bernoulli ( E-B ) equation allows us to be even more specific; i.e., for two vibrating bars of different materials, if the ratio E*k^2/Rho is the same and if the bar lengths are the same, the vibrational response will also be the same. Here, k^2 is the “radius of gyration of the cross section,” assumed to be constant over the length of the bar, and for a rectangular cross section, equals (a^2)/12, where a is the (constant) thickness of the bar.

As an aside, this result suggests a very interesting experiment that concertina reed makers might want to try. Make two different tongues of different materials (say steel and brass), with constant cross sectional area and having the same length and the same parameter E*(a^2)/Rho. According to these theoretical considerations, both tongues should produce the same acoustic sound: fundamental plus overtones. My feeling is that, if this conclusion can be experimentally verified, our understanding of the free reed would be significantly increased.

Is total mass of the gong would be the same also ? Or is it not important ?

For gongs, we are having another kind of discussion, for at least two reasons: 1) materials, and 2) governing equation of motion.

For gongs, metals can behave much differently than non metals. For instance, concrete is supposed to have many micro-cracks throughout its interior, and this will affect the “resonant” or decay-time properties of the gong.

Concerning the governing equation of motion for such gongs, since they are relatively thick, rotational aspects of small sections of the gong can be important. The Euler-Bernoulli governing equation neglects these rotational aspects, because the thickness of the bar it describes is presumed to be small enough, which is pretty much true. But for gongs, it’s often best to use a more precise formulation, called the Timoshenko governing equation.

One main criterion deciding which equation to use is to compare the thickness of the gong to the wavelengths of the acoustic frequencies one is interested in. As usual with acoustic phenomenon, certain “lengths” of the physical system become important, and the major criterion when such lengths become important is a comparison of such lengths to the wavelengths making up the acoustic result of interest. For a vibrating gong, I’d guess that one would be interested in frequencies up to around 10,000 Hz, which is an upper limit to the overtones average adult hearing responds to. Corresponding wavelengths here are about 3 cm, which is probably getting down to the thickness of practical gongs. Thus, one would expect that the Timoshenko governing equation should be used for gongs.

An aside here is to notice the difference between a vibrating bar, or the tongue of the free reed, and a gong. For the tongue, the frequency response required need not go above a couple thousand Hz, because it responds to only the fundamental of the music tone. The overtones are produced by the dynamical behavior of air flow. For a gong, the musical tone in the vibration must be able to respond to all the overtones, which occur at many times the frequency of the fundamental.

Thus, for a gong, it’s more appropriate to use the Timoshenko governing equation, which is more complicated than the E-B version. I was not able to find a clear way to write (display) these equations here, but anyone interested can refer to Wikipedia. The Timoshenko equation contains not only Young’s Modulus and density, but also the shear modulus, Poisson’s ratio, along with geometry, and all these parameters occur in complex ways. There is thus no simple way to relate gongs of different materials using the more accurate Timoshenko beam theory.

However, there is perhaps an intermediate approach considered by Phillip Morse, in Vibration and Sound, a classic text. In this approach, Morse considers a circular “plate,” which is the two dimensional analog of the vibrating bar, which as we have seen, can be represented well enough by the E-B governing equation. This restriction considers only a circular plate (gong) that is fixed at its periphery, although I don’t think this is the usual way to mount a gong. Regardless, this circumferential boundary condition, produces a governing equation much simpler than the Timoshenko formulation. With this “plate” equation, a comparison of different materials can be made in a way similar to that done with the E-B equation: as long as the parameter E*t^2/Rho/(1-p^2) and the gong diameter are the same, the response of two different materials should be the same. Here, p is Poisson’s ratio and t is the thickness of the gong. All these parameters are considered constant throughout the gong disk.

What makes bronze does not dissipate energy ?

I learned carbon fiber or more exactly epoxy does not waste energy when hit ? Is it true for e glass epoxy laminates ?

Thank you,

Umut

Although dissipation is a complicated issue, it must have something to do with the internal molecular structure of the material, and it is very dependent on the kind of material. I think Poisson’s ratio tells us something about dissipation because this parameter is a measure of the relative motion between microscopic elements. An incompressible material will have a maximum Poisson’s ratio of 0.5, and many metals have around 0.2 – 0.3. These values suggest that microscopic elements change volume when stressed, and this suggests dissipation. With metals, different kinds of dissipation are considered, depending how the stress tensor is modeled in relation to it. There are viscous, Coulomb, and hysteretic models, and one can find much description of these on the web.

For concrete, a common model for dissipation considers the relative motion between the sides of micro cracks in the material, which interestingly doesn’t degrade the material. This, I believe, is entirely different than the models used for metals, and thus, understanding why bronze is less dissipative than other metals may not give clues as to the dissipation in concrete. It’s my understanding that Bell bronze (approximately 70% Copper and 30% Tin) has been regarded as a desirable material for gongs and bells for over a thousand years or so, and this is based on empirical evidence. I don’t know how much scientific understanding is behind this practice, but the link below should provide you with some useful information (“A micro-structural model for dissipation phenomena in concrete”). I believe additives are introduced into concrete sometimes in order to increase its internal dissipation, as a way to make the material more resistant to earthquakes.

chrome-extension://oemmndcbldboiebfnladdacbdfmadadm/https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01194317/document

Best regards,

Tom

-

1

1

-

-

Hi Sami,

Would you please explain the columns labelled c.Nr.No. and # ? Thanks.

Tom

-

I don't think Dana is claiming that reeds made from UHB-20C produce a different sound than those made from 1095, but that they are less prone to losing their initial set or cracking. I suspect that could be explained by a difference in hardness and possibly grain size.Yes, I see. Thanks.

Although the part about the geometry might be worth more thought, concerning the comparison of timbre between two tongues of different materials. A simple experiment would be to make two tongues of the same material and pitch, but with different geometries.

Regards,

Tom

-

Modern steels like the UHB20C reedsteel I use are excellent. It shears very cleanly compared to straight 1095 spring steel and has the highest fatigue strength of any carbon steel. Supplied at Rockwell C 60 it is hard enough.

Hi Dana, from what I read, UHB-20C and 1095 are approximately equivalent (about 1% carbon, 0.25% silicon, 0.45% manganese), so I'm guessing the different properties you're getting in the steel you're using are mainly down to the heat treatment?

Hi Alex, from a purely theoretical point of view - granting that sometimes such a view might be too simplified - I don't think so. Both the Young's (Elastic) Modulus and density of both alloys are essentially the same, regardless of their heat treatment. Thus, the ratios of these two properties are essentially the same, and so, I'd expect their acoustic results to be the same, when fashioned into reed tongues of the same geometry.

Unless of course the geometries significantly differ, which is possible, since there are more than one geometries that can produce the same pitch. Thus, the material of construction is not the only thing to consider in comparing the sound of two different tongues. One must also consider their geometries, which I suppose complicates the issue quite a bit.

Regards,

Tom

www.bluesbox.biz

-

If I get this right, this is the first time I've seen a crimped-in tongue. The aluminum of the plate seems to be hammered something like a rivet in order to squeeze and hold fast the tongue at its root. Is that correct? If so and because of the low fatigue resistance of aluminum, I'm surprised this kind of fastening doesn't become unreliable after a while.

Regards,

Tom

-

Hi Mustafa,

I think this gong maker asks some very good questions. Of course, the surest way to answer them would be to build such a gong, so it seems you have an interesting project to delve into. I would suggest first making a small proof-of-principle model, maybe only a few inches in diameter. Make also a brass, or bronze one and compare the performance. I understand that traditional bell metals are a kind of bronze, about 80% Copper and 20% Tin, which produces an alloy with minimum internal dissipation (friction), providing a longer ring.

It's understandable to question whether a 60-inch diameter by 3-mm thick concrete gong would shatter. Thus, you'd want a cement mix of maximum strength, so I would suggest a pure cement mix, with a ratio one part cement and two parts sand. Strictly speaking, concrete contains aggregate (small stones), which I think would cause problems, unless they are much smaller than the minimum gong dimension (3 mm). This discussion takes me back to when I was a child. My father was a brick layer, and he gave my brothers and I a few lessons on mixing cement and laying brick. You should probably talk to someone who is knowledgeable about cement. For Portland cement, a 1 - 2 mix gives a mortar with maximum compressive strength, but I don't know about how the tensile strength varies. In your application, I think tensile strength plays much more of a role than with the usual applications. Adding stones (aggregate) to a 1 - 2 cement mix does not weaken its compressive strength, but it may weaken its tensile strength. There is a strong movement now to move away from Portland cement, because its manufacture produces a significant fraction of man made CO2 in the atmosphere. There thus may be other forms of cement appearing on the market now.

In fact, you might consider other stone-like materials. In dental work, they use (or they used to use) a substance called "stone" to make cast mouth impressions. This stone, like cement, is a powder mixed with water, though as I recall, it may be much less gritty and maybe even stronger than cement in tension.

Finally, with any material you use, since tensile strength is probably important, you might want to experiment with the addition of fibers. These fibers can be metallic or non metallic. If metallic, it should be non-rusting. If non-metallic, you can experiment with glass, aramid, and other plastic fibers used in making the many composites found in industry.

This thread has wandered quite a bit from concertinas, and perhaps most readers here would rather we take this discussion off the forum. You can send me a private message if you'd like.

Good luck,

Tom

-

1

1

-

-

Hi Mustapha,

I don’t think there is an error in my table. Pure silica glass does have high modulus and, if free of surface defects is extremely strong (high yield strength). The reason for the ? under the “Strength” column is perhaps because no one has tested such a material with a guarantee that there were no surface defects. There are many different ways to make carbon fabric, and they vary in cost and strength. The epoxy Novolac in the table is probably typical for that composition. You may have in mind the modulus of a single carbon fiber, which is listed at the very bottom of the table and is very high. For both glass and carbon fibers, single fiber strength or modulus greatly exceeds that of their composite forms. Lastly, we are not talking here of carbon nanotubes, which I understand are many times stronger than bulk forms of carbon fiber.

Along with modulus and density, an important parameter in the construction of practical reed tongues is the yield stress, or the fatigue strength, whichever is less. Thus, many materials may have interesting E/Rho ratios, but they also may be unable to handle the stresses caused by vibration. Thus, only some of the very strong plastics might work okay.

In order to answer your question about making a gong, we would have to look at the governing (wave) equation for a gong. Acoustically speaking, a gong can be referred to as a “plate.”

In diversion, acousticians have labelled vibrating objects according to the nature of the restoring forces that maintain their vibrations. The simplest is a “flexible string,” or simply “string,” in which the only restoring force is caused by tension. There is no “stiffness,” or resistance to bending. Next up is a “stiff string,” in which the primary restoring force is one of tension, as well as a “small” contribution from stiffness. Here, the stiffness forces produce only a small perturbation of the vibration that’s produced in a flexible string. Next up are “bars,” which the free reed tongue is a member of. Bars are the opposite of strings in that the only restoring force considered is stiffness, or the tendency to resist bending, with no contribution from tension. The examples here so far involve one-dimensional objects. The concept of a flexible string can be extended to two dimensions in objects called “membranes,” which like the string, have only tension as restoring force. We also extend the concept of bars to two dimensions, calling them “plates,” and like bars, have only stiffness (bending) forces restoring motion. I believe a bell could be considered a three dimensional plate, although for the very large bells (going up to hundreds of tons), gravitational forces may influence their vibrations.

Getting back to your question, the wave equation for a plate involves the material factor, (1 – s^2)*(Rho/E), where s is Poisson’s ratio, defined by the ratio of transverse strain to axial strain when a material is compressed or stretched. An incompressible material undergoing no deformation (stressed within elastic limits) will have s = 0.5. In practice, s for steel is 0.27 – 0.3, for brass is 0.33, and for concrete is 0.1 – 0.2. Thus if you plug in these material values to the factor containing poisson’s ratio, you get for steel 0.00878, for brass 0.0169, and for concrete 0.0147, where the units are the same as I used in the original table, and for concrete, I used E = 5.8 Mpsi, and Rho = 0.087 lbsm/in^3. The result here suggests, without any other considerations, a gong made out of concrete, for equal geometries, should sound more like a gong of brass than like a gong of steel.

If I may ask, what kind of concrete gong are you thinking of? How big? Besides the simplified acoustic discussion here, there are other practical issues that should be considered in planning such an object. For large gongs, weight might present special concerns. I don't know about the ability of concrete to withstand vibrational stress. There are people who study these things, and you might search them out.

Best regards,

Tom

-

1

1

-

-

Hi Mustafa,

As Alex said, you must consider both Young's Modulus and material density, although I believe it's only the ratio of Modulus/Density (E/Rho) that's important. The Euler-Bernoulli governing equation for the vibration of the reed tongue contains only the ratio of E/Rho, as far as material properties are concerned. The other parameters involve geometry (length and thickness). Thus for two tongues made of different materials yet having the same geometry, I speculate that the sound of these two different tongues will be the same, if they have the same ratio of E/Rho.

In fact, in 2012, I posted a thread titled, "Reed Tongue Materials - a Survey" on this site, and the link is: http://www.concertina.net/forums/index.php?showtopic=14568&hl=ttonon#entry138945 I'm happy to see that the original table of material's properties is still there. If you're interested in more on this subject, I suggest you read through this thread.

Best regards,

Tom

www.bluesbox.biz

-

Hi Harpomatic,

O Yeah, this guy is really good, and it never ceases to amaze me how musicians are able to find strikingly new ways of playing harmonica and guitar - two musical instruments that are blessed by the fact that they allow such enhanced intimate physical manipulation/interaction of the sound source by the musician.

Concerning my own disposition on the occurrence of double reed bends in the harmonica, I cannot assert that my experimentation is at all sufficient, and I must remain open minded. Perhaps, when the pendulum of interest again swings in that direction, I'll revisit the issue with more experimental ambition. Thanks for the updates.

Regards,

Tom

Titanium and stainless steel reed blanks

in Instrument Construction & Repair

Posted

David, interesting and impressive exhibit of laser cutting. Making such cuts in Titanium would be very difficult by most other means. Can you tell me the Ti and SS alloys they are made of?

I'm also curious whether there's any consensus on the acoustic differences between these and other reed plate materials. Does anyone here have anything to share in this regard?

Best regards,

Tom